Re-Used Tombs

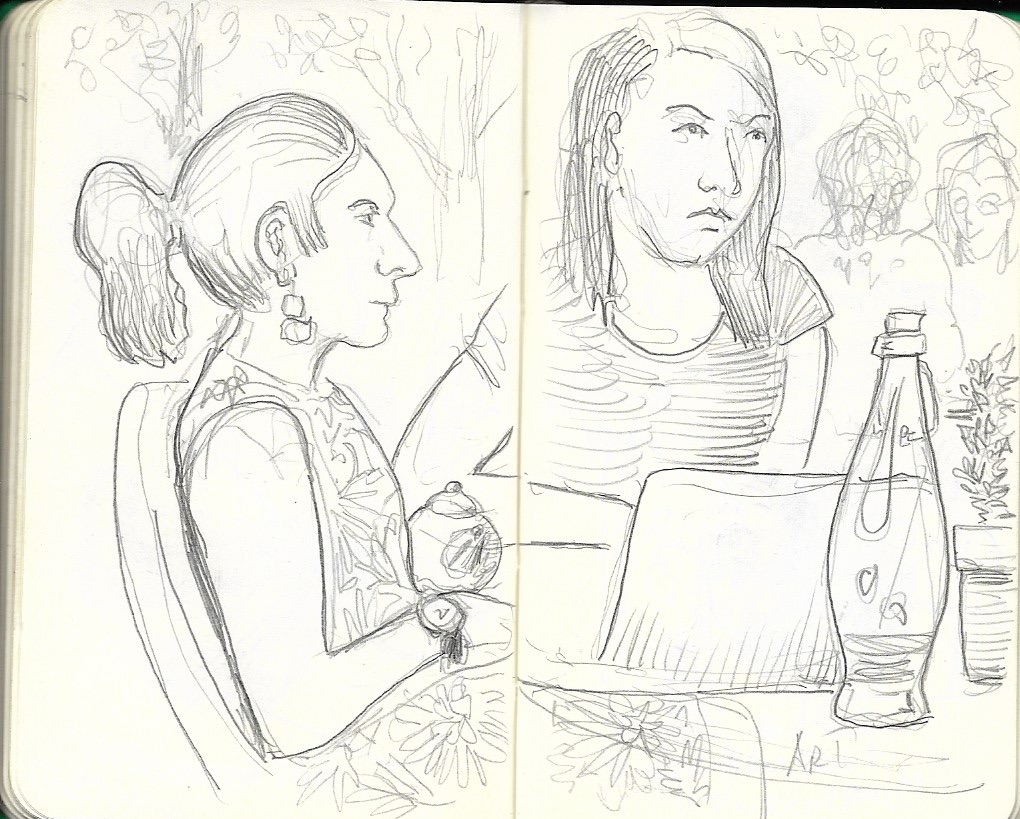

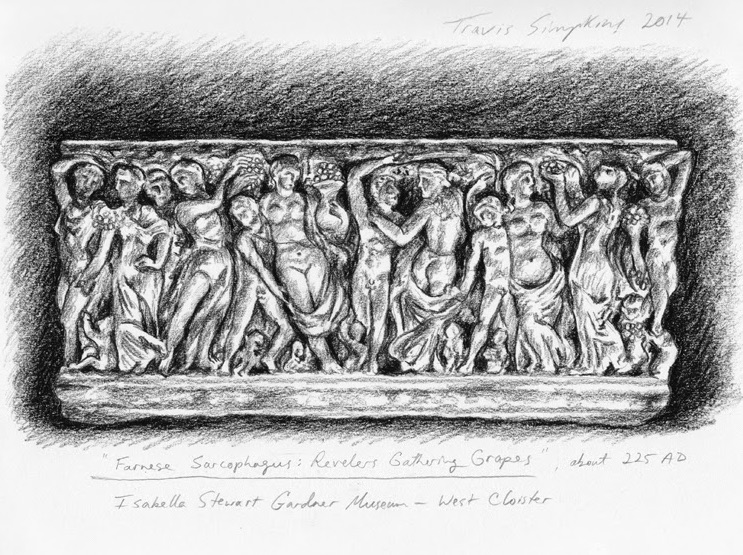

Two curators in the cafe of the Gardiner Museum in Boston. They are listening to a consulting conservator “mansplain” the process of preserving a Roman sarcophagus, part of the permanent collection of the museum. The Gardener Museum is the former private residence of Isabella Stewart Gardener and it features a spectacular open courtyard in which a variety of classical bits and pieces disport themselves among the hosta and ferns. One of these is a Roman tomb with elaborate carvings. Here is a sketch by a better artist:

Apparently the skylight above the courtyard developed a leak and the sarcophagus has been stained by rainwater: hence the need for a protracted lunch with a conservator on a hot day in July.

Why worry about the up-keep on a stone coffin two thousand years old? Primarily for its beauty. The twining figures, so vivid and sensual, bear baskets brimmed with grapes as they dance in attitudes of ecstasy around what once was a corpse, but now is only an expressive absence. How much work went into this erotic celebration of physical life, all for the purpose of commemorating someone now out of it. Perhaps it is that contradiction that adds to the power of the sculpted figures. They express our central dilemma as human animals: we have the imagination to understand our mortality, but we can’t change it. We can envision eternity, but not experience it. We can sculpt beautiful works that seem to transcend time and decay, but we ourselves vanish from the midst of them.

Which gets me to a favorite Rilke poem, from his Sonnets to Orpheus. In Sonnet 10 he is remembering sarcophagi he saw both in Rome and in the fields outside of Arles:

10

You, who have never left my feelings,

I greet you, antique sarcophagi

that the cheerful water of Roman days

flowed through like a wandering song —

or those others so open, like the eye

of an early awakening shepherd

full of silence and bee balm,

around which charmed butterflies whirl.

All that’s been seized from doubt,

I greet you: re-opened mouths

that knew what silence was.

Do we know it, friends? Or not?

Both answers build the hesitating hour

in the human face.

The tombs have been re-purposed as aqueducts and flowerbeds; once final and sealed, they are now open and fluent. But they also retain their old meaning. The final image of the human face shaped by its vacillation between knowing and not knowing is a powerful statement about what makes us human: our double consciousness, flitting (like butterflies) between death and life, between past and present, between being and becoming. We, too, are re-purposed tombs: we carry the form of our ancestors, through whose mouths we speak our living moment; after which we will return to the rich silence that is our earth.

Discover more from James Armstrong

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.