Autumn’s Deep Tone . . .

Two weeks ago I took a group of poetry students aboard a river boat for a morning’s excursion. I had brought my guitar along, just on the off chance that it might prove useful. About half-way through the trip one of my students picked it up and gave us an impromptu concert, mostly playing the folk songs of Gregory Alan Isakov. As we sat looking at the high river bluffs sliding past us in the thinning light of September, the plaintive blend of guitar and voice seemed to infuse the valley with significance. Now, my formerly Modern self would be quick to call that a projection of a human feeling onto a blank universe; but these days I question that kind of knee-jerk dualism. The song, singing wistfully (as most modern folk songs do) of the provocations and limits of desire, awakened my awareness of time and loss and the preciousness of the moment, a feeling inseparable from the swift passage of the river through the rugged scars of its own corrosive past, and from the green canopy of life, perennially knitting those wounds into a home.

This experience reminded me of a moment some years back, when I attended the Great Dakota Gathering, an event held in our river town every year. It is a time when indigenous people who originally inhabited the land are invited to return for a weekend of traditional dancing, drumming and prayer. The drum circle, with its attendant singers, is my favorite part of the weekend. The sound of Dakota voices bouncing off the bluffs opens a gulf in the day, revealing a vertiginous view of the deep past. We can read about Indian removal policies, but to hear the echo of a nearly-lost language amplified by limestone cliffs is to connect viscerally with what came before, and what remains. The Dakota experience was and is shaped by this Mississippi valley, and the valley was shaped by the Dakota–who farmed it, burned it, hunted it. The return of the Dakota sound brings me that reality.

Loss is real and continual, as is growth and adaptation, erosion and alluvial deposition. To feel something about a landscape is to acknowledge it as a source of consciousness–giver of metaphors and plots, provider of the coordinates and the subject of our narratives. Landscape is both agent and stage. Antagonist and dramaturge. Framework and substance. To feel this is not to “project.” Moods, as I have been saying, contain information.

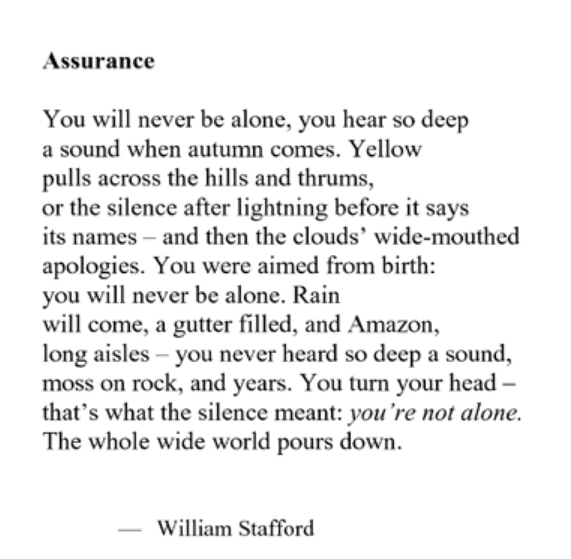

There is an odd little poem by William Stafford I’d like to insert here. At first glance it seems hopelessly naive, and the reader may understandably resist the “Assurance” the title promises. But, as usual with Stafford, the poem gets a bit more pithy as you read it over again.

To be non-Modern is to reject the false divide between human and world. This does not mean that you’ll be okay. Stafford’s poem says you are in the middle of a storm. You are like Lear, with the whole world pouring down on you. You are “aimed since birth” which implies there will be no rest until you quiver in the bull’s eye (and thus end your mortal career, to quote Thoreau). But you are not alone. Especially if you can hear the deep sound of the landscape. This is the only earth you get; you can’t escape it because at bottom you are it. It is intrinsic to your dreams, it is the shape of your intentions.

Discover more from James Armstrong

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

This rumination on existence as a modern or non-modern person echoes von Humboldt’s and Pope Francis’s view of the human condition…not apart from nature, embedded in it, and perceiving not just through data and reason, but our senses and emotions. That gives depth to living and connects past, present and future.