The Past Isn’t Dead. It Isn’t Even Past.

A sketch of a building on Newbury Street in Boston.

Something the Minnesota musician Charlie Parr said about the nature of time has stuck in my mind: in an on-line interview he describes time as being like the curl of waste aluminum coming off of a lathe, an image he gets from watching a craftsman mill a resonator cone for a steel guitar. Time isn’t linear, Parr says, it twists and turns and folds back on itself in unpredictable ways. We experience certain moments again and again, while others are left behind. Sometimes it even seems that the past is still ahead of us.

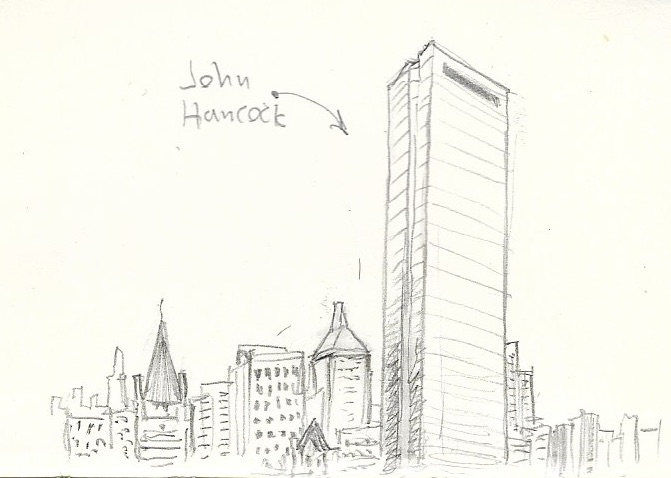

I am connecting this with my sketch of a building off of Newbury Street–Boston’s boutique-district which comprises 19th-century Back Bay mansions with slate roofs and sandstone gargoyles re-purposed as Anthropologie and Juicy Couture stores. It is only four blocks from Newbury to the John Hancock tower, a 60-story exemplar of the international mid-century modern style which overtook most cities of the world after the Second World War. The minimalist outlines and maximalist scale of the Hancock is typical of architectural modernism–the glass monolith looms over the Back Bay, an inscrutable alien presence. It is defiantly asserting itself as utterly dominant over its surroundings. This is how Moderns see the future.

For Moderns, the arrow of history flies in one direction and carries nothing with it. The future is a liberation from the shackles of the past: the theology of enlightenment requires that the future be the paradise that justifies this rupture. We are all hurtling toward freedom, toward a hard-edged world in which every decision is rational and every consequence known, a world freed from the shadows of superstition and fear.

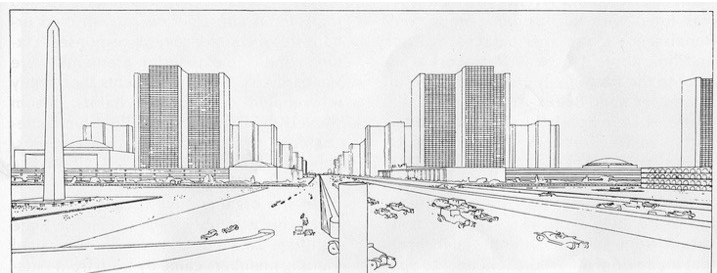

This is reflected in the cities Moderns imagine they will inhabit. The designs of visionary architects like Mies van der Rohe and Le Corbusier depict vast towers surrounded by sky and empty space. There are no previous styles in the radiant city of the future. There is no past. Like the Heavenly Jerusalem in the Book of Revelations, the city of the Moderns would descend and supplant everything existing before it with crystalline order.

Le Corbusier’s Radiant City

But all attempts to realize this future have had unintended consequences, not least being surprising resistance from the past. Many people instinctively recoiled from the Modern vision of the city; it seemed to them that on the one hand the human will dominated the landscape, but on the other humans had become insects, crawling in the shadow of their own triumph. It was surprising to architects to find out that people actually liked things to be at human scale, a revelation that happened often in the 1960s as critics like Jane Jacobs began to push back against the modernist consensus. The historic preservation movement gained tremendous influence from the mid-’60s on. When the John Hancock Tower went up in 1976, architects had to respond to public outcry that the building would cast a shadow on Trinity Church, a Registered National Monument. The past, it seems, had a vote when it came to determining the shape of the future.

Charlie Parr’s metaphor expresses this well: if time is not linear, but clumpy, recursive, then we are not so easily shed of it. Parr’s experience of time is informed by trauma–he has never quite gotten over the death of his father. His grief over that event has not been left behind, it keeps confronting him; it is in fact the mainspring of his art, as he was driven to write songs in reaction to his sorrow. But it is not only trauma that stays with us. One could also reference joy, or beauty, or any kind of intense fulfillment, the experience of which bobs in our wake but then is re-encountered ahead, flooding future moments with nostalgia but also with value. The memory of both joy and pain gives consciousness its significance and ensures that time is not the simple ticking of a chronometer. The human personality is almost entirely composed of memories–when we lose them we are no longer ourselves. What is death but the end of memories?

I thought of this recently while reading the reviews of Blade Runner 2049, the long-awaited sequel to Ridley Scott’s 1982 film. I have watched original Blade Runner many times. When it came out it was startling in part because of its complex vision of the urban future. The setting, Los Angeles in 2019, is rendered as a disorienting composite of rotting, abandoned buildings and sleek ultra-modern towers, of film noir detectives in raincoats riding in flying cars and Asian street vendors selling bio-engineered snakes. While science fiction films had sometimes depicted the city of the future as dystopian, in general the look had been in line with Modern fantasies–massive domes and pylons, streamlined trains and airships. Most had no street life to speak of, and certainly none featured dilapidated neighborhoods decorated in superseded architectural vocabularies.

A central source of Blade Runner’s hybridity is the set itself; for budget reasons, the movie was filmed on a pre-existing Warner Brothers’ set which had stood for years in a studio lot in Burbank and had been used in countless movies, including The Maltese Falcon. The set was called “New York Street Scene” because it reproduced a typical block of 1920s Manhattan. When director Ridley Scott began the pre-production design of his movie, he and futurist Syd Mead (who Scott had originally hired to design his flying cars) decided to update the New York set by applying an overlay of ducts and pipework to the original architecture, giving the impression of a world which was retrofitted, even jury-rigged. The future was a tangled encrustation appliqued over a dilapidated past.

This felt intuitively right: by the 1980s Americans were living in environments that were visually chaotic. When they went downtown they walked past 19th-century brick storefronts, Art Deco banks, and sleek glass modernist boxes. Americans lived in neighborhoods where Queen Anne mansions mixed with craftsman bungalows and cookie-cutter ranch houses from the 1950s; on the highway they drove past the “Googie” architecture of fast food restaurants and shopping plazas, often juxtaposed to farm houses and weathered barns. Beginning in the ’60s, huge swaths of urban infrastructure had been simply knocked down for parking lots or to make room for freeways, giving every city the look of having survived a bombing. In addition, many Americans had lived long enough to see once-modern buildings beginning to age, both stylistically and structurally. The average American city in 1980 seemed stuck between a past that had been half demolished and a future that had only been partially realized–or had been partially realized and then abandoned.

The bewildering visual contradictions of Blade Runner are thus the contradictions we all live with: Deckard, the eponymous Blade Runner, has an apartment with both a personal computer and an old-fashioned piano on the surface of which, next to his futuristic gun, are old photographs in antique frames and a stack of classical sheet music. There is a glowing orb of Saturn above an oriental rug. Past and present are all jumbled together–as it is in the street down below, where vehicles out of sci-fi comics share space with jingling bicycles ridden by people wearing coolie hats.

Of course, the contradictions of past and present are central to the movie in other ways. In particular, the plot centers on the question of what makes someone really human. Apparently a good way to tell an artificial human from a real one is to test for memory–at the beginning of the movie, Detective Holden says to the replicant Leon, whom he is interrogating: “describe in single words, only the good things that come in to your mind about… your mother.” This rather Freudian query is met with gunfire. It seems that the lack of a past is one of the things driving replicants crazy. Later, industrialist/inventor Tyrell tells Deckard his corporation is endowing replicants with artificial memories–“If we gift them the past we create a cushion or pillow for their emotions and consequently we can control them better” he says.

So central is this idea that memory is what determines humanity that at the climax of the movie, replicant Roy Batty, Deckard’s nemesis, asserts his moral superiority over the men who are trying to erase him by asserting the validity of his real–not his manufactured–memories: “I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe,” he says, “Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion. I watched C-beams glitter in the darkness at Tannhäuser Gate. All those moments will be lost in time like tears in rain.” This speech confirms that Roy, the artificial man, is completely human–more so than Deckard, as it turns out.

I titled this post with an oft-repeated quote from Faulkner. It seems more significant now than ever. Modernity assumes a clean future, divested of the past’s tendrils. The past is now pulling hard: American politics is being driven by ghosts from the Civil War and by the nostalgia of the white working class; the “Me, too” movement is dredging up abuses which the abusers thought were long buried; even our climate system is refusing to forget the past, as the accumulating effluents of our fossil fuel era begin inexorably to work our doom. Nothing is thrown away, nothing is forgotten. The more we try to make a clean break to the Utopian future, the more catastrophic the blowback, it seems. The model for our Modern moment, as Bruno Latour has said, is not Prometheus but Oedipus.

Discover more from James Armstrong

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Love the post! What’s your read of the new Bladerunner?