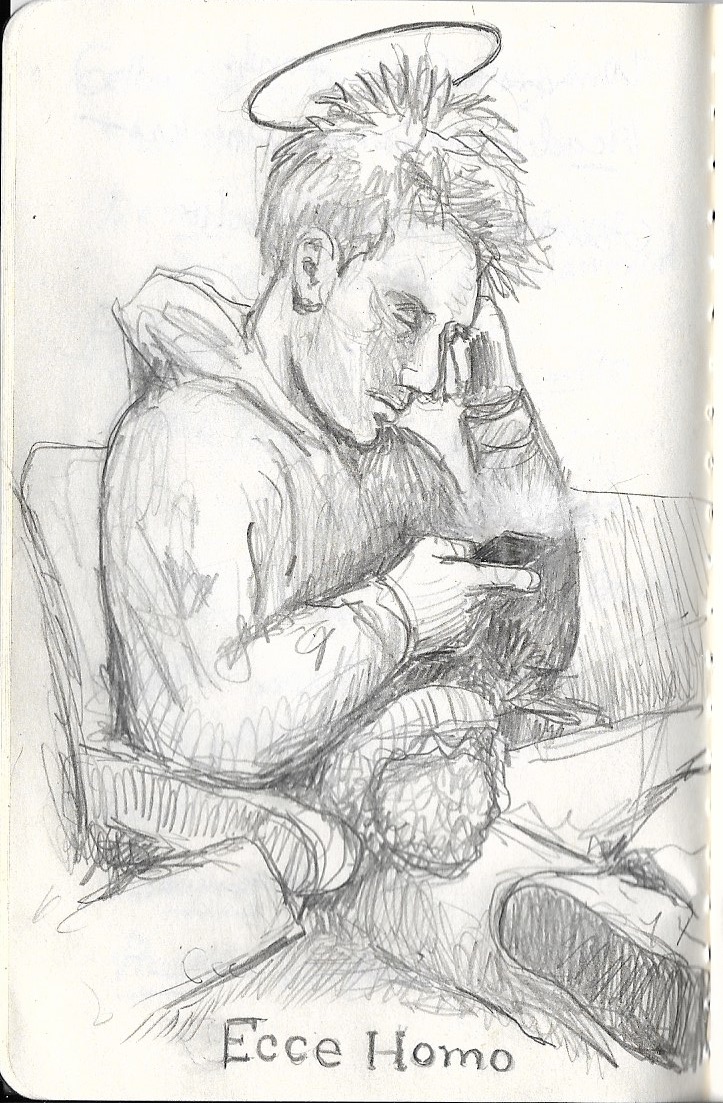

Ecce Homo, Amor Fati

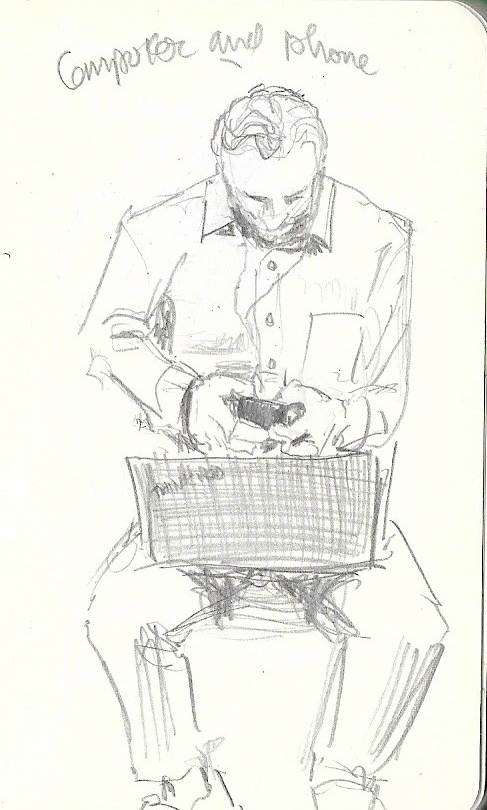

This guy was sitting a row behind me at a recent performance by the student orchestras at the University of Minnesota (my daughter plays viola in one of them). I sketched him for a good 15 minutes, during which he never once looked up from his phone. Something about the intensity of his engrossment prompted me to give him a halo and the Latin epithet which means “Behold the Man.” Ecce Homo is both a brand of late medieval piety, one in which devout people focused on depictions of Christ being exposed to the mockery of the Jerusalem crowd (“Behold the man!” is what Pilate says as he leads Jesus before the rabble) and the title of Nietzsche’s (self-mocking, self-promoting) last book. Nietzsche likes the phrase because it is laudatory and ironic at the same time–it conjures both triumph and ridicule and is tinged with martyrdom. I attached it to this man because I see him, locked in amor fati with his phone, as a martyr of sorts. A sacrifice to the complexities of late Modernity.

Modernity–privileging as it does mind over matter while simultaneously claiming only matter exists–specializes in producing loneliness. Moderns wander homeless among the material agents that invent and sustain them; the assumed inauthenticity of their subjective life leads them to doubt the authenticity of others–with whom they connect mainly through the brutal–but mathematisable–competition of the marketplace which Marx called “the icy water of egotistical calculation” that “resolved personal worth into exchange value.” No wonder mid-twentieth-century Moderns were frightened of being alone in a crowd (viz. books with titles like The Lonely Crowd)–this is not a formula for happy fellow-feeling. But at least loneliness left Moderns time to think. Now the crowd never leaves them alone. Thanks to the internet, Moderns are trapped in an incessant conversation with millions of others frantically vying to be “liked” and clicked on and responded to, all in a virtual space, far from those physical bodies doing the liking and clicking. Alone and crowded! A strange, anxiety-soaked achievement.

This man I have sketched is neither here nor there. He is not here because he is oblivious to his actual surroundings–but neither is he lost in his thoughts. He is somewhere between mind and world, on a flat screen, watching texts scroll by like marching insects. His problem is not alienation but engulfment. He is networked to a crowd whose every trivial thought is hurled at him with increasing rapidity. If he is on Snapchat or Instagram or Twitter or Facebook, then it is a preening, flattering crowd, intent on reducing him to a court sycophant. Like a character out of Dangerous Liaisons, he must present his best life, powdered, bewigged, rouged, to the judgment of others equally dedicated to self-promotion and capable of turning on him in a vicious, seething horde. Is he reading his news feed? Is he checking his bank account? Is he bidding for a snowblower on eBay? Is he looking for love on Tinder? Then it is a wheedling, conniving crowd, pressing in on him, amplifying his desires in hopes of robbing him of his time and money. The “icy water of egotistical calculation” has been heated and accelerated to a boiling torrent.

Worse yet, this man is addicted to the onslaught. Social media turns every smart phone into a dopamine-fueled slot machine. The intermittent reinforcement which the network affords mimics chemical dependency; statistically, this young man will likely check his phone 75 times a day and he’ll spend three hours–and very possibly up to eight hours– staring into it. He will check his phone within minutes of waking and it will be the last thing he sees before he falls asleep. This is a level of devotion lovers of old could not boast of–there is even a one-in-ten chance he has looked at his phone while having sex.

This is a radical twisting of what was originally meant by “the text.”

The picture below is Albrecht Durer’s rendering of St. Jerome, the man who translated the Vulgate Bible:

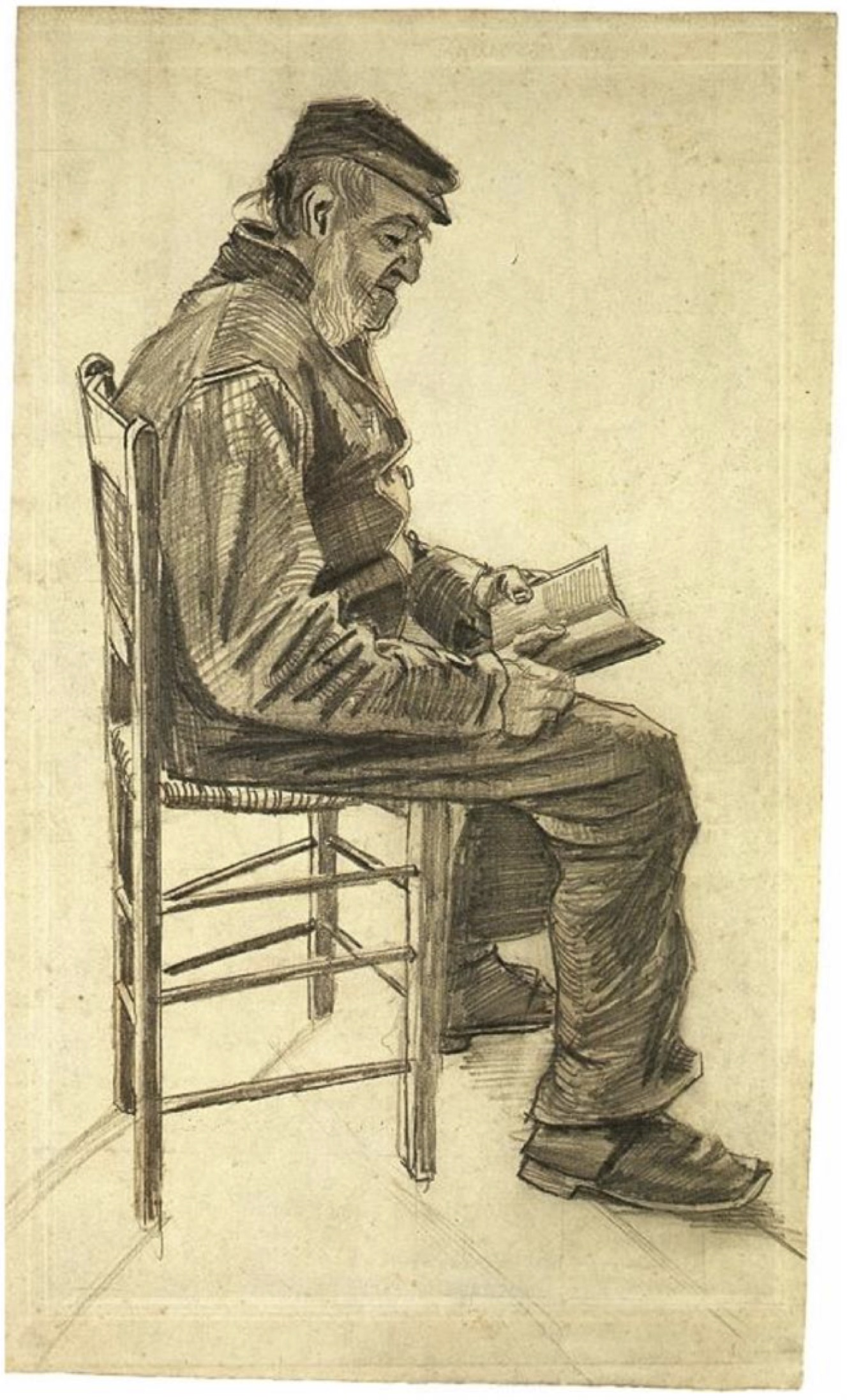

Notice the similarities in concentration: the downward look, the half-closed lids. But there is a profound difference between what the two men are doing. St. Jerome leans over a text that is utterly still. The text is not vaporous or reactive, it is inert. Whatever moves is his own doing, and what he is doing is shifting his attention between a text he is reading and a text he is creating as he translates the Bible from the original Hebrew and Greek into Latin–the common language of his day. He is combining what he receives with what he understands to create new content, but that new text will always only be a still object, a surface with marks on it. This object–this Latin text–will be replicated throughout the late Classical and Medieval world, but slowly, painstakingly, in the scriptorium (and later in the print shop). Human hands will copy strings of letters onto sheets which other hands will collate and sew into books, each one bearing the weight of time and materiality.

Also, notice that Jerome is alone. A book is an object that speaks, but haltingly, locally, singly. Books can network minds, yes, but they remain objects. Each book is unique; it bears traces of contact–marginalia, lunch stains, wormholes–and smells of vellum and dust. A book is a solid node in a ghostly network–like a bus stop on the spirit line. It is built of thoughts yanked from the stream of consciousness, but they have been halted and stilled and incarnated: one can shelter in their solidity. Others can gather there too–but only one at a time. A book is infinitely patient and will stand to one side for millennia, passively awaiting further visitors. The structure of printed text does not shift with time, or with interaction. That contact between the still and the moving–between text and person–is what has made the text so meaningful to civilization–stabilizing language, codifying belief, bolstering the state, and, with the spread of literacy, forming the Modern person. That is to say, the very idea of the individual, which is so central to Western notions of religion and politics, is in large part a function of literacy. As Walter Ong has said, unlike oral cultures, for whom language is irremediably social, in text based cultures “reading written or printed texts turns individuals in on themselves.” This is why Protestantism championed public education, the goal of which was to turn each person into an individual soul in solitary meditation over the Bible. Reading was a sacred rite of passage. Subsequently reading became a political rite of passage: democracy in its modern form is unthinkable without literacy, nor is industrial society. Science, law, politics, religion, all rely on texts–no wonder the United Nations has defined literacy as a fundamental human right.

Yet the written text owes its structure to oral culture. In his discussion of the shift from oral cultures to text-based cultures, Ong points out that oral cultures use elegance of structure to aid memory: without writing, “How could you ever call back to mind what you had so laboriously worked out?” he asks. The answer is to “Think memorable thoughts.” Oration is characterized by “mnemonic patterns, shaped for ready oral recurrence,” patterns such as balance, antithesis, rhythm, anaphora, consonance. Once writing began these patterns were transferred: what we call “good writing” has the hallmarks of memorable speech. The figures and tropes of rhetoric which have been part of the literary curriculum for thousands of years are based on hundreds of thousands of years of oral practice. Eloquence aids memory, quite simply, and even thought written texts to some extent made memory irrelevant, the physical difficulty encountered in reproducing and transporting books, and their irreducible singularity (only one person at a time can read an individual book), meant that memory still played an important role in written structure. When books are rare, one often has to remember them rather than own them. Moreover, reading (like oration) is linear, and longer texts require memory for comprehension. Reading the Bible, for example, necessitates that readers hold ideas and events from previous chapters in mind as they work their way through the vast labyrinth of stories, proverbs, laws, and prophecies.

In sum, the physical text, like the oration that preceded it, had to be carefully constructed in order to be comprehensible. Since artful construction takes time and effort, it was axiomatic that published writing was reserved for important content. Which is not to say that all writing was eloquent. The origin of writing is in record-keeping: advanced agricultural societies required a way to keep track of their storehouses of grain and pottery and weapons, so memory was outsourced to the clay tablets of scribes. No one needed, in a literate age, spend a great deal of time making an eloquent grocery list–though in oral times one would do so if one wanted to remember the items. The creation of un-artful language is thus to some extent a function of literacy.

One sees a gradual abandonment of memory-based writing as civilizations age; a good illustration being the decline in the use of poetry for mundane content. Many Greek texts on natural history, economics, agronomy, etc. were written as didactic poems. Lucretius’ On the Nature of Things is an example from the Roman period of a work of philosophy set to verse. As late as the 18th century the naturalist Erasmus Darwin (Charles Darwin’s grandfather) versified a botanical treatise called “The Loves of the Plants”–but today it would be unthinkable that a scientist would turn to verse to express his or her ideas.

But what happens when technology begins to invent new ways of recording and disseminating speech? Ong claims that with the coming of radio, phonographs, telephones, television and magnetic tape, technology had created something new, which he called “secondary orality.” This new form of orality differed greatly in scale:

Like primary orality, secondary orality has generated a strong group sense, for listening to spoken words forms hearers into a group, . . .But secondary orality generates a sense for groups immeasurably larger than those of primary oral culture-McLuhan’s “global village.” Moreover, before writing, oral folk were group-minded because no feasible alternative had presented itself. In our age of secondary orality, we are group-minded self-consciously and programmatically. The individual feels that he or she, as an individual, must be socially sensitive.

Much of the twentieth century was consumed with this new orality, as broadcast media played an increasingly important role in social organization. At first, media reinforced eloquence, as transmissions were not repeatable; but with the rise of recording technologies, oral communication was freed from memory–and to some extent from eloquence, especially since it was occurring alongside a vast production of written texts. In secondary orality, one exploits the emotional immediacy of personal delivery, but no longer is disciplined by the formal demands of primary orality.

This leads to an noticeable shift in expectations for public communication. The fact that one does not have to be memorable when communicating means that one can be “informal” –i.e. unstructured, non-repetitive, spontaneous. When informality is allied to the warmth of presence, the result is a kind of illusion of intimacy. Intimate speech is elliptical, allusive, telegraphic because the close relation between communicants provides context. Many things are unsaid because they remain in the storehouse of shared experience–events, beliefs, aspirations can all be “pointed to” without being described. When public communication mimics this intimacy in its embrace of informality, inarticulacy begins to signal close–therefore authentic–relationships.

One can trace this by comparing the rising informality in the discourse of American presidents; from, for example, the speeches of Wilson, which where extremely formal and had to be written down and disseminated by newspapers, to the “fireside chats” of Franklin D. Roosevelt, which made use of the “secondary orality” of radio and happened right in people’s living rooms– to the television version of such a chat Jimmy Carter gave in 1977 in a beige cardigan (demonstrating that visual information was beginning to play an increasingly important role). In the twenty-first century, it is a short distance between George Bush deliberately mispronouncing the word “nuclear” to the ungrammatical, misspelled Tweets of Donald J. Trump. Clearly something quite profound has happened: Trump’s supporters feel a degree of intimacy with him purely as a result of the medium he is using.

I would argue that social media like Twitter and Instagram and Snapchat have moved us to what I would call “tertiary orality”: a stage where public communication lacks the memorable structure of orality because it leans on the permanence of text and lacks explicit content because it pretends to intimacy. If secondary orality convinced us to be “group-minded self-consciously and programmatically” in ever-larger groups, tertiary orality highjacks language and uses it to serve primarily as an incessant reinforcement of group belonging. Tertiary orality mimics intimacy because its use is not to develop thoughts or arguments but to simply mark one’s place in a social network. The average text takes less than five seconds to read, so there is literally no there there. Yet 913,242,000 of these minimal texts are sent every hour of every day worldwide. It is not their content but their status as action that matters. This is part because human beings can’t actually be intimate with more than about 50 people. Social media, with its capitalistic love of expansion, tries to employ the discourse of intimacy to push the user past the possibility of intimacy. If Marshall McLuhan famously said “the medium is the message,” we might say the message is “I text, therefore I am connected.” Affirmation, confirmation, are all that is required for the most part. Like the reassuring caws of agitated flocks of crows, most messaging is conducting the primary business of holding the group together. The result is the social enshrinement of inarticulacy and superficiality as a signifier of belonging. This would explain the widespread use of emojis, which essentially replace linguistic structures with visual symbols, and this would certainly explain Snapchat messaging, which is largely sub-literate. It would also explain the over-use of exclamation points, all-caps, and other textual devices that are the equivalent of speaking more loudly when you think you are not understood. It is a language of likes and dislikes, a language that points to content but never conveys it. In this it resembles most the parlance of advertising (which got to false intimacy as a mode long before the internet). What is texting and Snapchatting and Instagramming but the parlance of the commodified personality?

To return, finally, to the young man depicted above, the martyr who began this conversation: he is scrolling and clicking and swiping right–he is passing on gossip and terse rejoinder and trivial commentary on his status that once would have been reserved for the ephemera of breath. And yet does he have time for reading the texts painstakingly carpentered to outlast the flood? Does he have time to be alone with either his own thoughts, or the thoughts once deemed worthy of remembrance?

We have entered the age that we might call “the tyranny of the thumb.” What can’t be said by a thumb isn’t worth saying. Many will admit that this is frustrating, even debilitating at times. Yet we must love it! Moderns must accept the Modern! Ninety-five percent of people under 25 have phones–a truly remarkable market penetration. I mentioned in my first paragraph the phrase amor fati, which is translated as “love of one’s fate.” Nietzsche was an expositor of this idea, as he puts it in Ecce Homo:

My formula for greatness in a human being is amor fati: that one wants nothing to be different, not forward, not backward, not in all eternity. Not merely bear what is necessary, still less conceal it–all idealism is mendacity in the face of what is necessary–but love it.

It seems that we are to take this world of phantom intimacy, this swarming embrace of a needy and demanding virtual crowd, as the condition of our time. I feel that gravitational pull as I walk through the world, among those who gaze into their hands. Yet I still don’t carry a phone most days (and when I do it is an antique flip phone). I have never learned to text.

I do carry a sketchbook.

The tyranny of the thumb

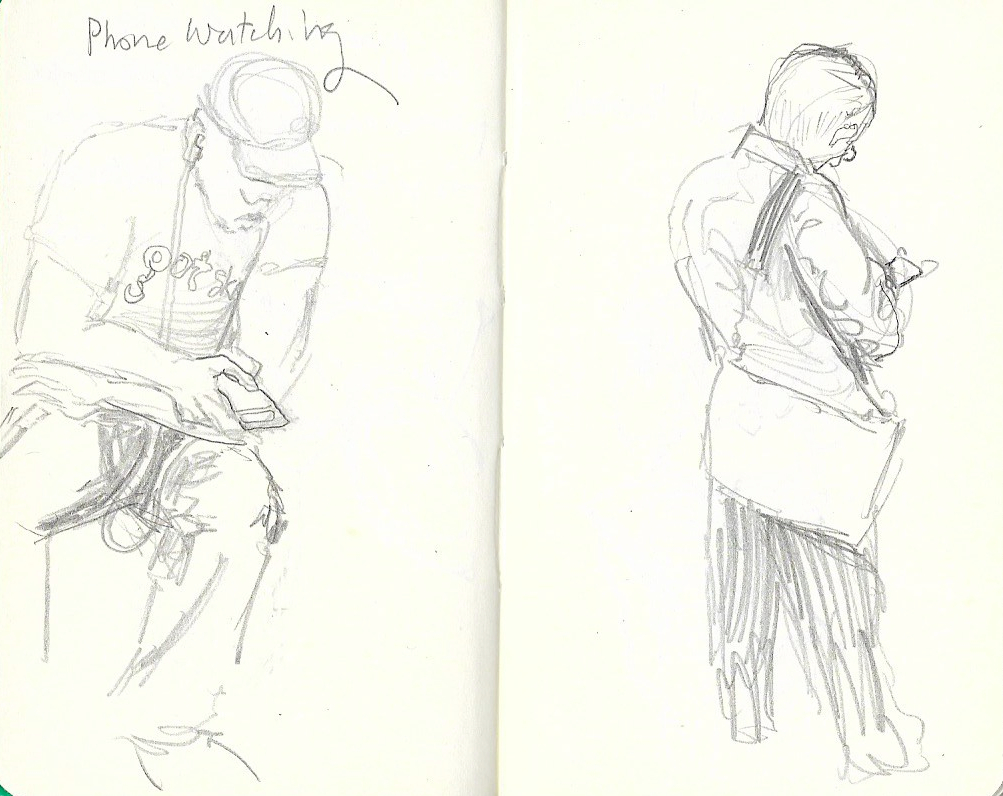

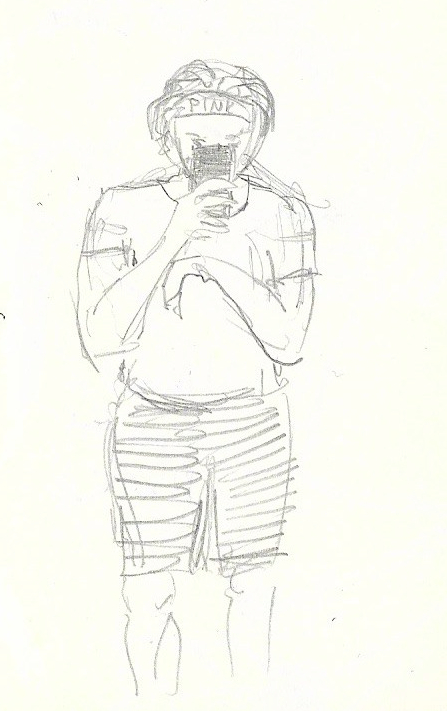

EXHIBIT A. Sketches from the Boston Trolley

People watching their phones. Are they different from people reading books or newspapers? Am I imagining it? Do I see obsessiveness, anxiousness in the phone-watching-face?

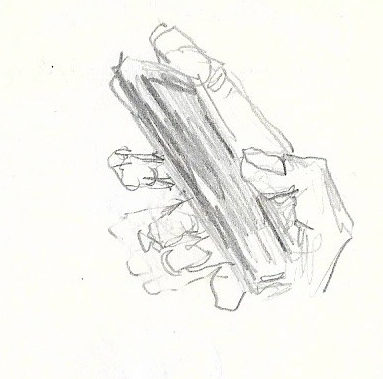

Sometimes the phone is like an eclipse.

This guy is part of a “three body problem.” He has made his communications frantic in a non-linear manner.

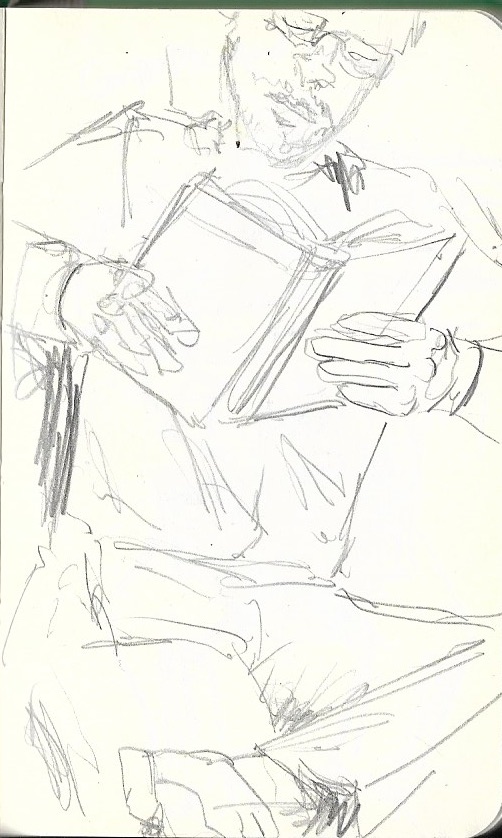

Here’s a guy reading a book. He looks more relaxed to me. When he’s reading he’s “in” the book, but the book is not actively pursuing him. It is not intermittent, or preening. It is just there. He knows it is an object.

EXHIBIT B.

Sketch by Vincent van Gogh. Because we always need a sketch by van Gogh.

You carry a sketchbook….and you have learned to blog. I think we all need to remember we have choices about how much we get sucked into the digital void. Not sure if the digital natives know this, but we digital immigrants at least remember alternatives and can conceive of choices—like simply not being on Facebook…ever.

I promise, I did not read this on my phone. Lots to think about here, well done!

Yeah: I don’t hate the internet. I benefit from it every day. But I don’t go there for social confirmation. I go there for research. My students on the other hand almost never use it for serious purposes, and their addiction to their phones has kept them from learning how to read.

I wrote this on an Android phone because I was traveling. I read your blog on my phone, too. Pretty essential in business work these days. Strangely, in my creative contemplative work–writing poetry–I use a phone, notebook, and computer. When flying (the only time I can spare to edit my poetry) I read my poems on my smartphone, record the needed corrections in my notebook, and make the changes on my laptop in the hotel or back at home on an early Saturday morning. So for me these devices are essential tools. On the other hand, I’ve felt the siren pull of Facebook when I get an email notification that somebody I know has posted something interesting. Once there, I am sucked in…scrolling past the minutiae to find the gold nuggets of information. Ten minutes go by before I notice I’m lost. Then I shut the damn thing down and get back to real life. But I have found some interesting articles people post as a result of random scrolling. Not research…just skimming the surfaces and gleaning a few choice items, like a swallow darting back and forth low over a pond. I am merely human and distractible by shiny objects. Dare I say it? “Phones don’t kill reading skills, people kill reading skills.”