Reform

I spent Earth Day playing folk music and manning a booth at our local celebration, which was held in conjunction with the Saturday farmer’s market. Despite the unseasonable cold, it was a jolly gathering of mostly the same people I see at all liberal-leaning events in our small Minnesota city. People were buying organic vegetables and picking up fliers about solar power, climate change, and pollinator-friendly gardening. There were booths selling hand-made jewelry and the like. One organization was giving out free tree saplings, another was handing out free starter plants for vegetable gardens. There was a sense of loose social unity, but in the Age of Trump it seemed hard to believe that wearing a hemp necklace and planting a choke cherry tree would move the needle much. We seemed stuck in two worlds: one that believes we need to radically change, to move away from the corrupt, self-destructive fossil-fuel-guzzling status quo, and one that wants to double down on the that same system, seeing it as the source of prosperity. This had me thinking about the Protestant Reformation.

Last November my wife and I went to see the Minnesota Orchestra perform a series of works in commemoration of the 500th anniversary of Martin Luther’s Protestant rebellion against the Catholic Church. The evening started out with Bach’s Second Orchestral Suite, featuring Adam Kuenzel playing the intricate the intricate twiddles of a fugue. As always, I was left imagining a formidable and impassioned candy box.

Bach’s music is the essence of the 18th century Protestant world-view, one that embraced middle class order and decency, empowered by a newly rationalized view of nature and society. With the collapse of Christendom’s central authority, the Papacy, the new nation-states of Europe had to find other sources of political unity. Perhaps for the first time since the Roman Empire, Europeans turned their idealism to this world, rather than living in anticipation of the next one. Luther removed celibacy as a requirement for the priesthood and dissolved the monastic orders: as a result Christians could suddenly embrace procreation and the family in a way that was only provisionally possible in Medieval times. The emphasis on scripture as the sole authority in spiritual affairs (sola scriptura) made reading the Bible central to religious life and therefore encouraged ordinary people to become literate and to explore their individual faith. The Reformation made the church local and participatory again: church music of the early 15th Century was “sung in Latin by the clergy in the church choir stalls. The reformers aimed at giving music back to the people – to all worshipers, including the women,” according to the Virtual Museum of Protestantism (which is a trip in itself, if you want to wander the dreams of the Reformation, French-style). The result was an explosion of music composed in the vernacular, performed and sung by the community it was written for. Bach is the high end of the movement, as he was subsidized by the aristocracy (and was criticized for being too intricate). But the blending of the music of the court with the music of the people is still part of his legacy, as every child who has had to play Bach on a rented instrument in a local school concert can attest.

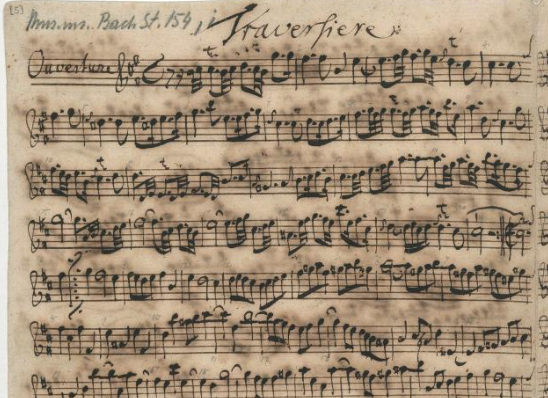

Here is the opening of the Second Orchestral Suite in Bach’s own hand, so you can hum along (this is from the Bach Digital website):

Of course, this cheerful narrative elides the chaos of the Wars of Religion (of which there were nine in France alone). In the next 150 years, 10 to 20 percent of the population of Europe would die in sectarian violence. Much blood flowed before the calm notes of Bach.

We might see the obsession with order that is so noticeable in Bach’s music as a reaction to the extreme disorder that preceded it. In fact, the entire Enlightenment might be seen as a response to Christendom’s great civil war. This is the subject of a fascinating book, Stephen Toulmin’s Cosmopolis: The Hidden Agenda of Modernity. Toulmin argues pretty convincingly that Modernity’s insistence that nature is rationally structured and that society should follow suit is a result of trauma experienced by the generation that had suffered through religious war. Nature became “Nature,” a supreme authority that could be invoked without dissent. As Nature was God’s creation, it was religious, but not theological: the “book of Nature” could be read by science instead of by religious partisans. It was the great unifying concept that helped patch together Europe by making Europeans Moderns. Although this concept would drive the movement toward secularism, it was not secular at the outset. Thus, I hear in Bach’s music the sublime reassurance of the clockwork universe, complex and various but always moving toward a predetermined unity.

Which brings us to the second work performed by the Minnesota Orchestra that November night–Mendelssohn’s “Reformation” symphony, which was written in 1830 to commemorate the tercentenary of the Augsburg Confession. Which is what? you may ask if you are not a Lutheran. The Augsburg Confession was a response by Martin Luther and his associates to a demand from Holy Roman Emperor Charles V that the breakaway Princes and Free Cities of the new Lutheran movement explain their new belief to him. Which they did in the city hall of Augsburg. Charles V was hoping to resolve doctrinal differences in order to unite Europe against the Ottoman Empire. His tactic didn’t work, and instead the Lutheran “confession” became the central document unifying the Lutheran faith– the wars of religion would soon follow.

Why would Mendelssohn write a symphony about Luther’s confession three hundred years later? The conflicts fueling the Reformation kept rumbling underneath the peace of Westphalia, which ostensibly put an end to the religious wars in 1648. King Wilhelm Friedrich III of Prussia was planning to throw a big celebration in Berlin. Wilhelm was ambitious to make Berlin a center of European culture, and he was also hoping “to unify Calvinists and Lutherans into a single Protestant liturgy, thereby strengthening its political influence against the Catholic church,” according to conductor Michael Lewanski’s helpful notes on the Reformation symphony. Prussia had emerged as a political power capable of unifying the German people, and Friedrich was hoping to use religious unity to help solidify that power. Mendelssohn was the scion of a prominent Jewish family that had converted to Protestantism; he was also an ambitious composer. The symphony would serve to both further his musical career and affirm his commitment to the Lutheran ethos.

The party in Berlin never happened, and Mendelssohn’s composition would not be played until 1832. At the time it was not well liked; a premier in Paris was cancelled because, according to the Chicago Symphony’s program notes, “the musicians found the score unplayable (‘much too learned, too much fugato, too little melody,’ was one verdict).” But it has become popular in the ensuing years, especially with Lutherans. The composition features two popular melodies, well-known to church going audiences: the “Dresden Amen,” a series of six ascending notes popular with liturgical choirs, and Martin Luther’s famous composition, “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God.”

The symphony enacts, one might say, the struggle of the Reformation: Lewanski refers to the development mode as “a crisis and out-pouring” of “deep and conflicting emotions” that are resolved by Luther’s melody “as if to suggest that not only faith, but the power of music as an expression thereof, is a savior.” The symphony ends with, Lewanski says,

a full-throated, almost too insistent chorus of the entire orchestra declaiming the hymn at first in unison, then in a traditional harmonization. It is a striking claim — rather than music as an agent of transcendence, here it seeks to affirm and unify the social order with the religious in [a] way that only a composer like Mendelssohn, born and raised a member of the only recently emerged bourgeoisie, whose family were Lutheran converts from Judaism, was in a unique position to have imagined.

This expression of social solidarity was very apparent in the audience that night, as a great many middle- and upper-class Minnesotan Lutherans (the whole night had been partially underwritten by a Lutheran arts organization) were palpably aroused by the symphonic affirmation. Conductor Osmo Vänskä caught the fervor of the moment. Always an emotional conductor, he seemed a whirlwind of passion on his little platform:

The musicians, too, played with Romantic fervor.

The audience at the finale roared its approval. Doubtless many of the Lutherans in attendance were only Lutheran by family tradition, the winds of secularization having swept them clean of their faith. Others may have been descendants of various flavors of the Reformation–Methodist, Presbyterian, Congregationalist–and many were doubtless Catholic, either confessionally or culturally. But for a moment the hall was united by the dream of einheit that Mendelssohn was orchestrating. That is one of the supreme effects of music.

After the intermission came the much-anticipated premier of RE-FORMATION, a choral symphony specially commissioned by the Orchestra for the anniversary of the Lutheran revolution. Composed by Sebastian Currier, RE-FORMATION is described in the program notes as a work which “recalls the past—incorporating fragments of Mendelssohn’s Reformation Symphony—while also looking forward, ending with a choral hymn that encourages us to protect our natural environment for future generations.” This of course attracted my interest, and was the main reason for my being there. I am always on the hunt for art that attempts to address our looming environmental predicament. In descriptions of the work, Currier is explicit about his intention to do just that. As the program notes say:

Currier was particularly struck by the connection between Psalm 46—the basis for Luther’s Ein’ feste Burg text—to modern environmentalism. “In the Psalm’s first stanza, God’s strength is depicted by his ability to save us from the ravages of a destructive natural world, from apocalypse,” he notes. “Considering the world today, this viewpoint is reversed. We cannot stand by idly and permit our actions to destroy the planet. We need to take action.”

Wow. Okay. Would this be the kind of clarion call we needed? Would it help mobilize our energies in the direction of change?

Unfortunately, no. And the reasons for its failure are worth considering, as they arise from the limitations of Modernity itself.

I am not a music critic, and I am pretty much your standard oaf when it comes to classical music. Perhaps, had my ear been more refined, I would have been able to, as the New York Times critic did, experience Currier’s work as “harrowingly effective.” But instead I found it a dissonant, self-mocking morass. Moreover, I was conscious that this effect was by design. The composer’s own notes (from his publisher’s website) indicate his intention: “As RE-FORMATION begins, we hear fragments from Mendelssohn’s Reformation Symphony ring out amidst a more obscure sound world, like decaying structures in a ruined landscape.” The “ruined landscape” is not expressly defined, but we can pretty much assume that Currier is critiquing the bourgeois affirmations that Mendelssohn forged out of his first and second movements. That is, Currier is to some extent dissing the very feeling of social union that moved the audience to thunderous applause before the intermission.

Since the beginning of the 20th Century it has become axiomatic that high art must be suspicious of those grand gestures which unified Europe in the previous century. The crisis of faith in Western Civilization began in the late 19th century as the internal contradictions of Modernity began to emerge: first, the rise of scientific challenges to Biblical narratives (and especially Darwin’s new mechanism for creation) began to erode the faith in, well, faith. Moderns discovered that, having installed Nature as an inarguable authority, they didn’t particularly need the authority of scripture, or even the idea of God, to wield that authority. Moderns believed themselves to possess, for the first time, objective knowledge of Nature, which they felt distinguished them from all other societies; Modern political and moral life would be based on sound reasoning and objective facts, not superstition or blind tradition. This new belief empowered a growing secularity which ate away at religion and traditions alike.

However, for a long stretch of the 19th Century Christians and secularists alike were committed to a belief in Progress. The great imperial projects of globalization and industrialization, combined with the rise of technical expertise and the bureaucratic state needed to enact it, seemed to promise the “heaven on earth” that in some ways Luther was enabling when he married Katrina von Bora, an ex- nun, in 1525. Bourgeios business in this world could be a noble calling, and could be part of God’s plan for universal uplift. However, by the end of the 19th century, intellectuals came to the realization that the West represented not just enlightenment, freedom and democracy but also imperialism, exploitation and fratricide. The “civilizing mission” that had been seen as The White Man’s Burden looked, when stripped of its veneer, a lot like the rapine of global capitalism. You can see this revelation at work in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, to name a prominent example. Kurtz’s final words, “The horror! The horror!” are expressive of how a lot of intellectuals felt about newspaper accounts of European atrocities in the Belgian Congo and, by extension, about injustices occurring throughout the entire project of the European imperium. Finally, when Europeans turned on each other with machine guns and mustard gas in 1914, that was the end of any optimism about civilization’s grand march forward.

The resulting intellectual suspicion of grand narrative and of bourgeois demands for cultural solidarity is thus understandable, even morally laudable. But it tends to create a major problem when an art form is asked to perform the old task of unifying, rather than critiquing, the audience. Modern art and literature have been especially skilled at skewering, lampooning, deconstructing bourgeois society. The prevailing methods have been fragmentation, bricolage, and pastiche: “These fragments I have shored against my ruins,” as Eliot says in The Waste Land. The main point has been to present a broken mirror to society, so that it might awaken from its dream of unity and take up the burden of self-knowledge. We might say that the prevailing mode is tragedy, rather than comedy or heroism. But in the Greek usage, the tragic mode was supposed to remind audiences of the transcendent power of the gods and the limits of human power. The secularism of late Modernity meant that tragedy now presented the audience with an anagnorisis but no higher dimension to appeal to.

According to the program information, RE-FORMATION is a fairly standard modern product:

In RE-FORMATION composer Sebastian Currier and writer Sarah Manguso continue this process of using material from the past and reconfiguring it to suit contemporary needs. In 1517 Luther’s predominate concerns were the corruption of the papacy and an individual’s relationship to God. In 2017 Currier and Manguso recast Luther’s concerns from the sacred to the secular: to the environment and the urgent need for humans to take responsibility for the safety of the planet. As the piece unfolds, this lineage becomes apparent. We first hear a fragment from Psalm 46 sung in the original Hebrew, then the same fragment in a Latin translation from Roman times. Following this is the first phrase of the Martin Luther in German, and then a translation of the Luther, from the time period, into English.

This does make a kind of sense. Environmentalism is seen by most people as a reform issue: Modernity must be adjusted so that our industrial civilization can come to “care for Mother Earth.” The problem with this comparison is that Luther was reforming the Church by pushing it back to what he considered to be its original purpose. He believed that the Church of his day was corrupt, and needed to be put back on course. This sense of returning to original purpose is antithetical to Modernity, which does not seek to return to an original state but attempts to assert a radical break from the past. “Reform” for Moderns can only mean doubling down on a belief in objectivity and rationality–a belief which, increasingly, seems to be a source of new conflicts rather than a solution. But for a secular society to admit the limitations of human reason and will is to, in a sense, enter a cul de sac where neither Nature nor God are helpful. As Nietzsche realized, the result is nihilism.

It is in this sense that the language of environmental politics is so fraught. Are we fighting for Nature? Nature is everywhere and everything, so why does it need a savior? Are we then fighting for human survival? Darwin told us that already, and what does that have to do with protecting species? Moreover, some wish to cling to the older, more theistic Modernity in which science was the handmaiden of the Church (for example, most Fundamentalists are of this persuasion–stuck in ideas about God and Nature that animated Descartes and Newton but fell away after Darwin. This explains the seeming contradiction of their embrace of modern technology and their hatred of evolution). Everywhere the contradictions are growing more pronounced. The “Radical Right” is correct that there is a lot of strange religion in environmentalism: most environmentalist are animated by some notion of the sacredness of creation which is hard to explain scientifically. And of course, people on the Right don’t admit there is a lot of strange religion in their camp as well–an irrational hybridization of Ayn Rand, Leo Strauss and American evangelicalism, to be exact). With this fraught background in mind let us examine the words Sarah Manguso penned for Currier’s choral section of RE-FORMATION:

Black sky, forgive us.

Black sea, forgive us.

Black earth, forgive us.

Orb rushing dead through the silent night,

all cinder,

forgive us.

First of all, we can see how Nature has revealed itself to be just another name for God, who is being asked, in the guise of sky, sea, and earth, to forgive us for our transgressions. You can see how this might be confusing to Christians and scientists alike. Second of all, a dead orb is not a likely rallying point for consolidating political action. Manguso is seemingly describing Mars, rather than Earth. Contrary to her vision, the earth is not a “cinder”–not yet–and the geosciences all tell us that the planet is a very robust agent with a long history of spectacular comebacks, so it is extremely likely to outlive our current troubles. Moreover, if it is dead, we are surely dead–unless we are somehow in heaven looking down? The confusion compounds.

Passing over our objections to the talk of a “dead orb,” the next stanza is much more dynamic and seems to presage a bio-resurrection:

Deep in the ash of the grave of the world

Where nothing is,

We pray for the sound of new being to sound.

For one bright drop to swell—

For life to seethe, green-blue,

flowering endlessly.

Which might be something we could get behind. But notice the next move Manguso makes:

We will unfoul the waters,

the sky, the terrestrial marrow.

We will unpoison the heart of everything that is.

The poem has moved from utter helplessness and a cry for forgiveness to a kind of human triumphalism, almost a paeon to geo-engineering. Here is the modern problem: Nature is sometimes all-powerful, invoked as the final authority, as the source of “laws” that govern us, and sometimes utterly passive, tractable, random, and meaningless. It is both the source of all value and the negation of all value–often at the same time! RE-FORMATION concludes its choral section with an attempt to weld this great contradiction together, asking first that Nature wake up (implying it is passive and inactive) and then that it “have mercy” on us, implying we are the helpless ones who need it to save us. What a weird contradiction! The last lines sound as if Joseph Priestly had rewritten the Catholic mass as some sort of deist rite:

Light, decorate the heavens.

Benevolent system, awaken.

Have mercy. Have mercy.

This is not so weird really, if you see it as revealing the contradiction at the very heart of Modernity and therefore exposing the source of our feckless inability to deal with the existential threat of climate change. No wonder, then, that at the conclusion of RE-FORMATION, members of the audience were noticeably unenthused. After being reassured by Bach and brought to their feet by Mendelssohn, they were both confused and somewhat affronted by the message of the composer. And I don’t blame them!

We desperately need a new Reformation–our current one is on its last legs and cannot address the dangers we face. We need a new unifying vision, but it won’t be found in Modernism, or Post-modernism.