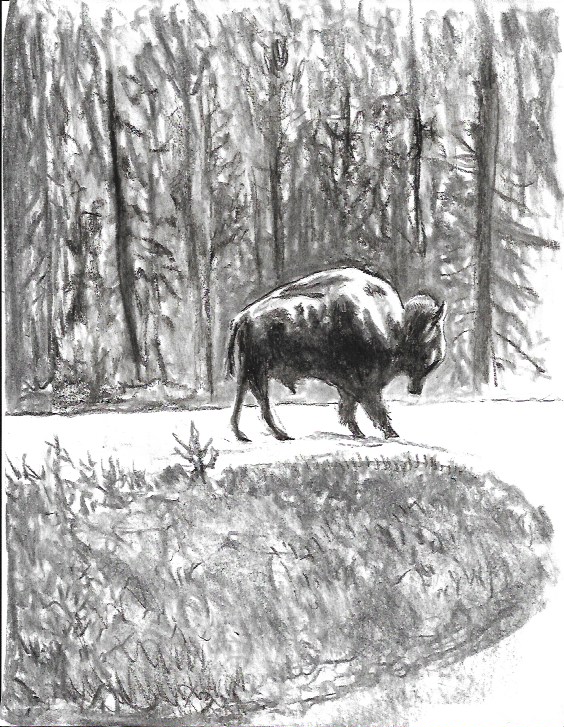

Buffalo Jesus

An American Bison blocking traffic on the Chief Joseph Scenic Byway outside of Yellowstone National Park.

Buried in the torrent of election news this past week was the World Wildlife Fund’s report that between 1970 and 2014, the world’s population of vertebrate animals has declined on average by 60%. Ed Yong, at the Atlantic’s website, makes this a bit more visualizable:

Since the 1980s, the giraffe population has fallen by up to 40 percent, from at least 152,000 animals to just 98,000 in 2015. In the last decade, savanna elephant numbers have fallen by 30 percent, and 80 percent of forest elephants were slaughtered in a national park that was one of their last strongholds. Cheetahs are down to their last 7,000 individuals, and orangutans to their last 5,000.

We are rapidly approaching a future where most of the wild animals you and I grew up reading about will be found only in zoos. And the cause? I think we all know. The question is, why don’t we feel, in our hearts, that this is real? I don’t mean why can’t we acknowledge the facts–if you are reading this, you are probably aware of climate change and habitat loss and you probably want to do something to “save the planet.” But still . . . a recent poll found that while 70% of Americans think climate change is happening and will endanger future generations, only 40% think it will harm them personally. We discount future harm at a furious rate. And when the average American looks around, he or she sees a lot of deer (in fact this time of year in Minnesota they are a menace on the roads), and there are plenty of raccoons, possums and coyote. It is hard to believe we are in a crisis when it is not happening in your backyard.

But we also are Moderns. The foundational assumption of Modernity is that our rational understanding of Nature will enable us to control it. Since that is a core article of faith, somewhere in the back of our minds we believe that we are heirs to a future paradise of managed plenty–the future our tech companies keep promising us. And perhaps we feel that if we lose a few animal species in the process, well, that is sad, but animals are not on the same level as humans.

This is abetted by Judeo-Christian tradition. The two stories in Genesis which narrate God’s creation of the world both make it clear that Man is on top. In the first story, God makes humans on the sixth day of creation, and it is clear that they are to rule:

Then God said, “Let us make mankind in our image, in our likeness, so that they may rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky, over the livestock and all the wild animals, and over all the creatures that move along the ground.”

In the second account, Adam is made before plants and animals–so he is even more important. Animals are created in an attempt to provide humans with help and companionship: “The Lord God said, “It is not good for the man to be alone. I will make a helper suitable for him.” This is the story of Eden, the garden where Adam named the animals and lived with them in peace. Until that incident with the apple, of course.

Both accounts are stories told by an agricultural people. Religious stories always reflect the world as it is experienced by the people that tell them: it is not surprising that ancient Hebrews–farmers and herdsmen–would think of the world in these terms. Life is a garden, watered and controlled by a Master Gardener. Sin is a result of violating farm rules. Nor is it surprising that those stories have made sense to our forefathers and mothers–human history over the past 11,000 years has been one of ever-increasing agricultural success. We have asserted our dominion over the plants and animals. We have hijacked the productivity of the biosphere and used it to expand our human footprint until we have become the most powerful biological–and even geological–force on the planet.

But our garden metaphor is getting us into trouble now. A garden is inherently a place of exclusion and simplification: whatever isn’t useful to us is exterminated. But a garden is only successful because it exists in the larger fabric of the biological world. Gardens always fall victim to entropy: they are short-term schemes. Their exclusiveness is not sustainable. The secret to success in nature is diversity because the random forces that threaten life are relentless. No one species has the key to survival, and no one member of a species does either. We can’t actually say what is useful to us, in the long run. Moreover, life creates its own luck through interdependence: the rise of flowering plants, for example, was coeval with the rise of pollinating insects. Each made the other possible. As is true in human economies, natural economies thrive by creating new niches through constant innovation and diversification. Propped up by fossil fuels and addled by a simplistic model of the world, we are simplifying ourselves toward extinction–and taking everything with us.

We need a religious metaphor that expresses our reliance on the success–and resilience–of other species. Fortunately such metaphors are available: humans have only been farmers for a tiny fraction of their time on earth, and there remain many traces of the spiritual beliefs of hunters and gatherers. I have commented elsewhere on the insights pre-agricultural people had about the genetic unity of life–insights that resurfaced with Darwin (https://thinearth.blog/2017/08/23/we-dont-believe-darwin-yet/). In America we are lucky to have, close at hand, the spiritual beliefs of Native Americans to help us get beyond our garden story. As Joseph Epes Brown puts it in The Spiritual Legacy of the American Indians,

In the multiple expressions of Native American lore, in myths and folktales, in rites, ceremonies, art forms, music, and dances, there is the constant implication of, indeed direct references to, the understanding that animal beings are not lower, that is, inferior to humans, but rather, because they were here first in the order of creation, and with the respect always due to age in these cultures, the animal beings are looked to as guides and teachers of human beings–indeed, in a sense their superiors.

Moreover, animals are seen as co-creators of the world. Brown points to a particular example of this in the widespread Algonquin tale of the Earth Diver. In this story, Earth Maker Nanabozo enlists the help of the aquatic animals to help bring dry land into being. Each animal in turn dives down, trying to find a grain of earth from which new land will be made. Usually it is the muskrat that succeeds, surfacing with mud in his paws. This story, says Brown, “shifts the orientation away from creation understood as a single event of time past, to the reality of those immediately experienced processes of creation ever happening and observable through all the multiple forms and forces of creation.” This is much more consistent with our biological stories of origin and change.

Brown goes on to say that “In the people’s intense and frequent contact with the powers and qualities of the animals including birds and eventually all forms of life, humankind is awakened to, and thus may realize, all that an individual potentially is as a human person.” If this is so, it is not just our biological safety we are putting at risk when we drive the world’s animals to extinction; we are also becoming less human.

But we don’t necessarily have to leave Genesis behind. We can use this perspective to see in the biblical account echoes of the older, pre-agricultural beliefs. For example, God makes animals so that Adam will have helpers, and so he will not be lonely. That implies a deeper connection than simple domination. We can also see the remnants of an animal creation story in the character of the snake who talks Eve into trying the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge. According to some Christian theologians, this act, while letting in sin, also allowed humans a chance to become something better. Known as the doctrine of felix culpa, the fortunate fall, this interpretation claims that, in the words of Saint Ambrose, Adam’s sin “brought more good to humanity than if he had stayed perfectly innocent.” That would actually put the snake in the role of Trickster Hero, would it not?

To bring animals back into our religious faith would be consonant with the Christian effort to sacralize the physical world. If the great opposing heresies–or competitors–to the early church were the gnostics and neoplatonists, for whom the physical world was either evil or unreal, Christianity sought to cling to the physical importance of creation. This is reflected in the central Christian rite, the mass of holy communion. To anyone outside the faith, it is a grisly-sounding practice, flirting with cannibalism, as Christians are exhorted to eat the body and blood of Christ. But the idea of the sacrificial feast is old, and is directly linked to the central mystery and agony of life: to exist, we must die, and from our death others are nourished. This is the only condition under which life is possible. We have become immune to the central paganness of the mass, because the church has long veered away from biology and into abstraction (perhaps the subtle triumph of neoplatonism, as some have suggested). But any Plains Indian would understand, looking at Jesus on the Cross, that the Sun Dance is being reenacted there: “Only in sacrifice is sacredness accomplished; only in sacrifice is identity found.” He would also trace a connection between the Christian mass and the feast of the sacred buffalo, whose sacrificial death gave life to the Indian people.

I write this the day before the election. Some of you will read this before you vote, many others will read it after the event. It is an indication of the turbulence of our current situation that the difference between those two moments will be like the difference between being on one side of a mountain and another. Timescapes can be radically different–some eras are level plains, on which the transition between one hour and another is hardly noticeable. Others are like the highly eroded landscapes I witnessed out West: complexly folded, containing drastic variations: high plateaus, deep, sunless declivities; sudden drop-offs, knife-edged ridges. It is clear that we currently live in the badlands of the nonlinear, and any trust in the gentle unfolding of the next moment is ill founded. Whatever happens, however, is part of the biological (and sacred) story of this thin earth we share. Make sure you are trying to find your place and a place for your community in that story, if you want it and you to survive.

Discover more from James Armstrong

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.