WINTER DREAMS

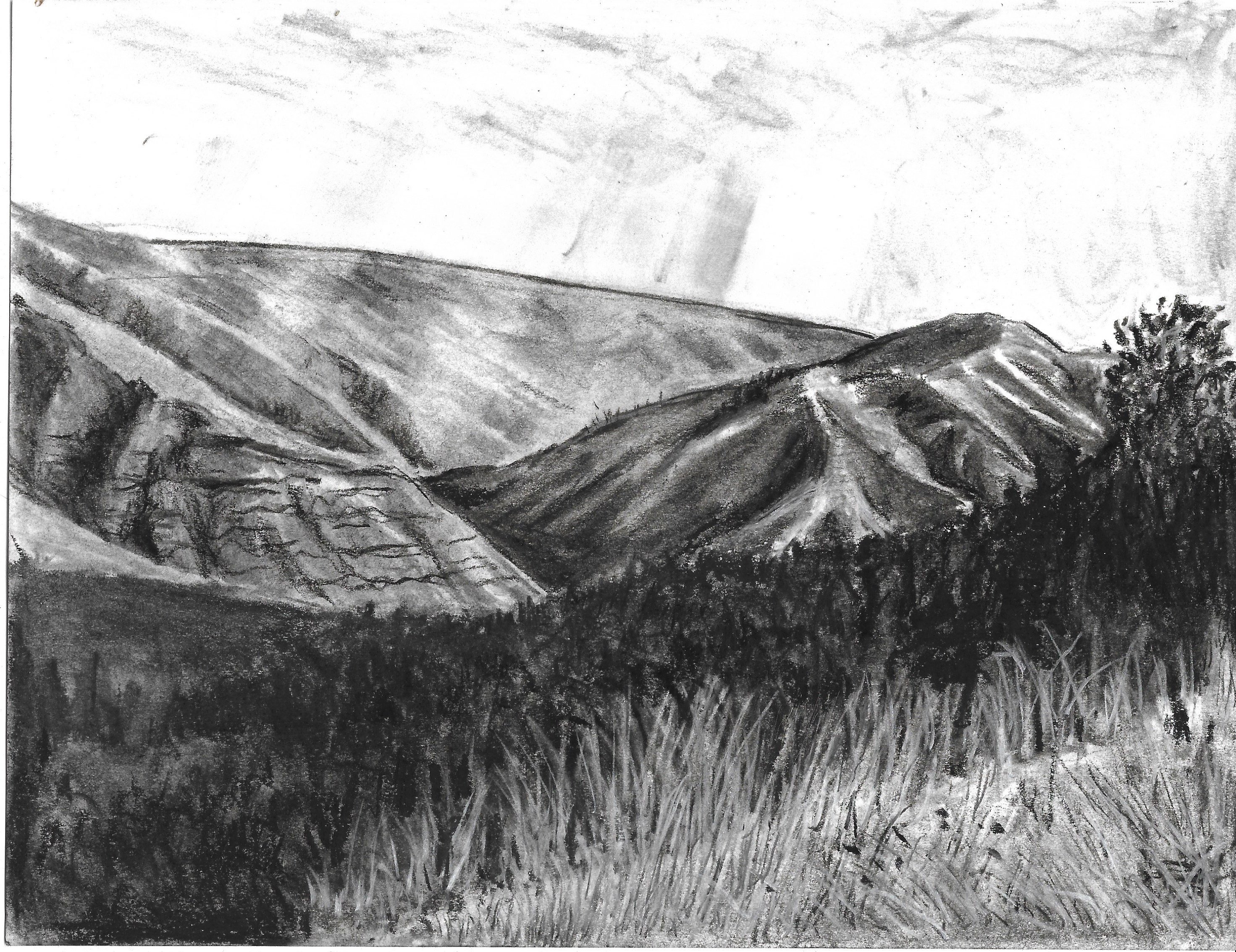

If you follow Highway 3 north out of Enterprise, Oregon, you first meet a sign that says “no gas for the next 72 miles.” The road rises through the empty brown hills of the Oregon shortgrass prairie and sage steppe, passing the entrance roads to vast ranches. Gradually you reach the Ponderosa pines of the Wallowa-Whitman Forest. About 40 minutes in, the land on the right suddenly drops away and you are on the edge of a stunning canyon of intricately folded mountains. The Nez Perce called this area saqánma, which means “long, rough canyon.” At the bottom runs Joseph Creek, on its way to meet the Grande Ronde River, where the families of the Wallowa Band made their winter camp. Deep in the canyons they were protected from the harsh winds and snow and they survived on cached food–dried meat and salmon, dried berries, biscuitroot and camas bulbs. They spent their days listening to “myths and stories which were inhabited by a cast of characters that included animals, plants, rocks, rivers, celestial bodies, and other figures who behaved like humans in a pre-cultural era before humans were created” (American Indians of the Pacific Northwest digital project).

We can see a connection with the winter traditions of Northern Europeans, traditions which have engrossed many Americans in the past months: huddled in our houses with our decorated trees, we too have been retelling our myths and thinking about spiritual things. In the Germanic tribes of the north, winter was a time when people survived on preserved foods–Hallowe’en, in fact, marked the time when herd animals were slaughtered and processed as hams and sausages, and when fall vegetables were pickled or dried (hence our predilection for fruitcake!) to stave off starvation in the harsh winters. With the coming of Christianity, Christmas, the celebration of Christ’s birth, was moved to December by the early Church in order to take advantage of the Roman Feast of Saturnalia, a Mediterranean version of the same kind of holiday. Saturnalia was marked by a sacrifice at the temple of Saturn in the Roman Forum, followed by feasting and merrymaking. The Roman Saturn was the agricultural god of the Golden Age, when Romans believed their ancestors gathered the bounty of the earth without strife or want. Saturn organized the fauns and nymphs–the local deities of animal and plant life, as well as of rivers–and gave them laws. Thus Saturn was the original founder of Roman prosperity, and his temple was the site of the Roman treasury.

Everything comes back to the bounty of the earth, which ancient peoples knew had to be respected and venerated. For the Nez Perce people, this connection was still direct. Their relationship to the world around them blended the practical necessities of hunting and gathering with the spiritual connection to those sources. Like the Plains Indians, the Nez Perce believed in tutelary spirits which individuals either inherited from an ancestor or encountered during a vision quest. These spirits were usually spirits of animals who interested themselves in human affairs: “The Nez Perce believe that although the animals became mute after humans arrived, they could still reveal their full power to humans in visions and dreams” (American Indians of the Pacific Northwest).

Something of this survives in the Christmas story of the animals in the stable: on Christmas Eve, it was said, animals could talk. The donkey and the ox bowed their heads to venerate the Christ Child. The old carol, “The Friendly Beasts,” had the donkey singing “I carried His mother up hill and down,” and the cow sang “I gave Him my manger for his bed.” Supposedly this song originated from a French feast day in honor of Mary’s burro, the Fete de L’Ane (props to Mentalfloss.com for this information).

But Christianity came late in human history, when the connections to hunting and gathering, and to the wilds, were attenuated. The success of Roman factory farming (using slaves and conquered land) had distanced urban Europeans from the realities of the biosphere. The history of Moderns, funded as it is by fossil fuels, has only exacerbated that alienation from both the practical and the spiritual connection to the landscape. Thus, here we are, in 2019, on the brink of ecological collapse because we are incapable of seeing our vulnerability. Our detritivorous habit of living off dead plant and animal matter from the Mesozoic and Paleozoic has blinded us to our dependance on living beings. It has also made us spiritually alienated from everything around us.

The Nez Perce could not understand why white settlers built permanent settlements on the uplands and suffered through the harsh winters of the exposed high plains. They scratched their heads at the arrogance of a people who thought they could subdue the environment by force of will. Their close attention to the realities of their world taught them that such lonely arrogance was maladaptive.

It is not very likely that we Moderns will survive by doubling down on our current strategy of denial. We are being forced to attend to the voices of the biosphere, which are speaking louder every minute. As we exit from our holiday revelry into this Roman month of January, we need to listen. Winter dreams are not just pleasant wish-fulfillments. They also bring prophecies.

Discover more from James Armstrong

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.