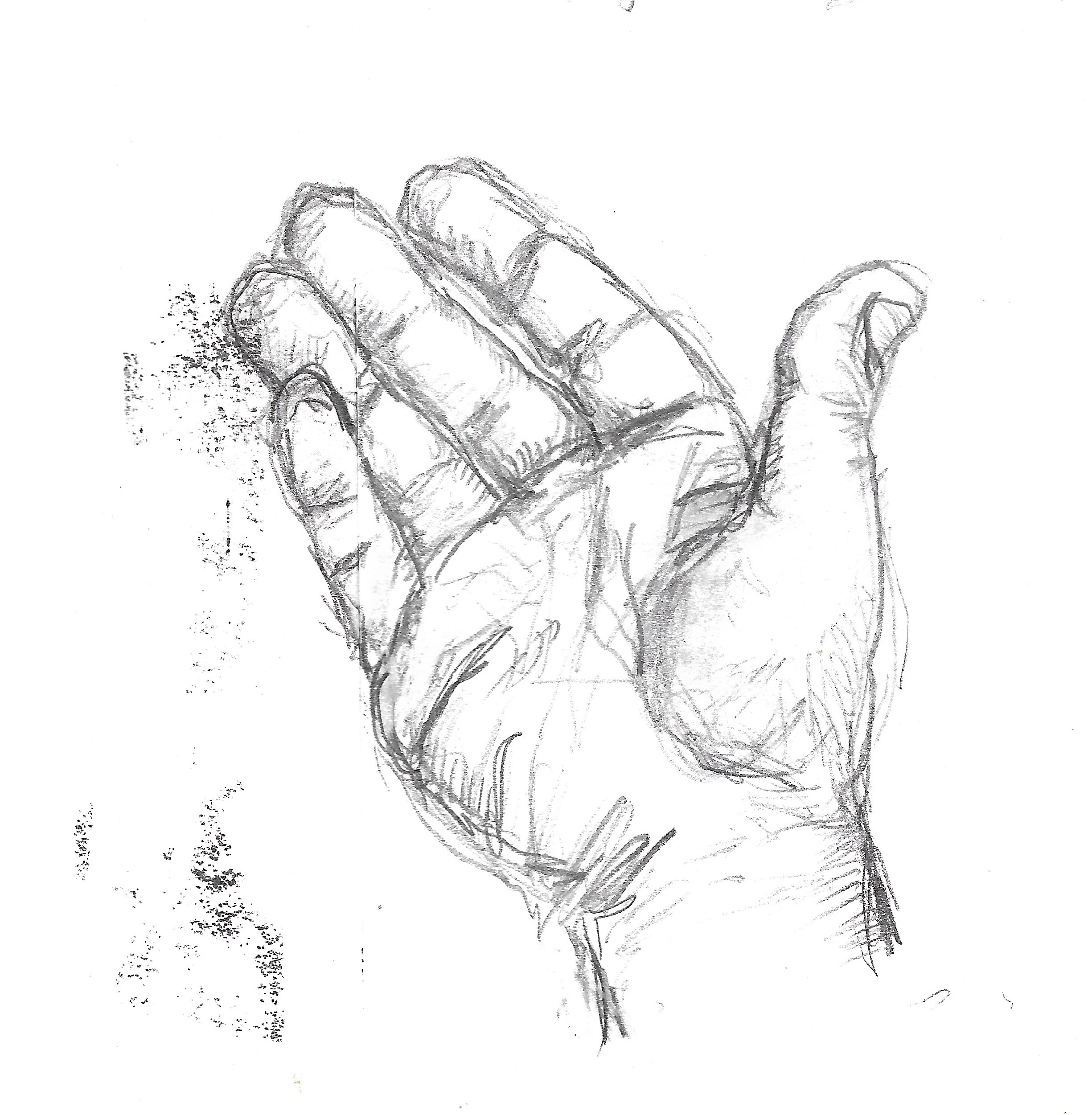

The Loyal Hand

A not particularly good but somehow compelling drawing, done on the back of an envelope.

Why am I obsessed with this drawing? It was just a throw-away sketch, something I did on scratch paper while sitting at the dining table. But I find myself looking at it often. I am not a very observant person, for the most part. I am in my head a lot of the time. This drawing forces me to see my own hand. See it as my hand.

How often do we actually look at our hands? It is a peculiar facet of consciousness that we are only aware of that which we are attentive to. Consciousness is pragmatic: it is employed for specific tasks. We are aware of what we intend to do, or of what might threaten or aid us in our purpose. If we had to be aware of everything in our environment we would be completely overwhelmed. Thus we live with our bodies every minute of every day but are only aware of them when they are causing us specific sensations of pleasure or pain, or when we are having to use them for unfamiliar or especially difficult tasks. The rest of the time our relationship to the body is subconscious and automatic.

One powerful effect of sketching from life is that the focused attention required in order to render the world on paper in two dimensions causes us to experience with awe a world we usually ignore. Background suddenly becomes foreground. In this respect, sketching is a religious act, or at least akin to altered states of consciousness which are often called religious. To draw your own hand is to have it suddenly, uncannily, present in a manner similar to certain drug experiences: everyone knows the cliché of the stoner gazing in wonder at his own hand.

But this sketch I’m posting is not fascinating solely because it drags into consciousness something usually ignored. The human hand really is something special. Lately I have been studying the work of George Herbert Mead (1863-1931), one of the founders of American sociology. In the posthumously-published Mind, Self and Society, Mead considers the evolutionary origins of consciousness, and claims the hand plays an enormous role in the development of the mind–specifically it enables humans to conceptualize the world as made up of separate things. “The hand is responsible for what I term physical things,” Mead writes. Because we “handle” the world, the world is experienced as made up of parts. By way of example, Mead says “If we took our food as dogs do by the very organs by which we masticate it, we should not have any ground for distinguishing the food as a physical thing from the actual consummation of the act, the consumption of the food.” Because humans grasp their food; they are “manipulating a physical thing,” which is a “universal” because it is distinct from the act. Thus the hand creates the thing: “We thus break up our world into physical objects, into an environment of things that we can manipulate for our final ends and purposes.”

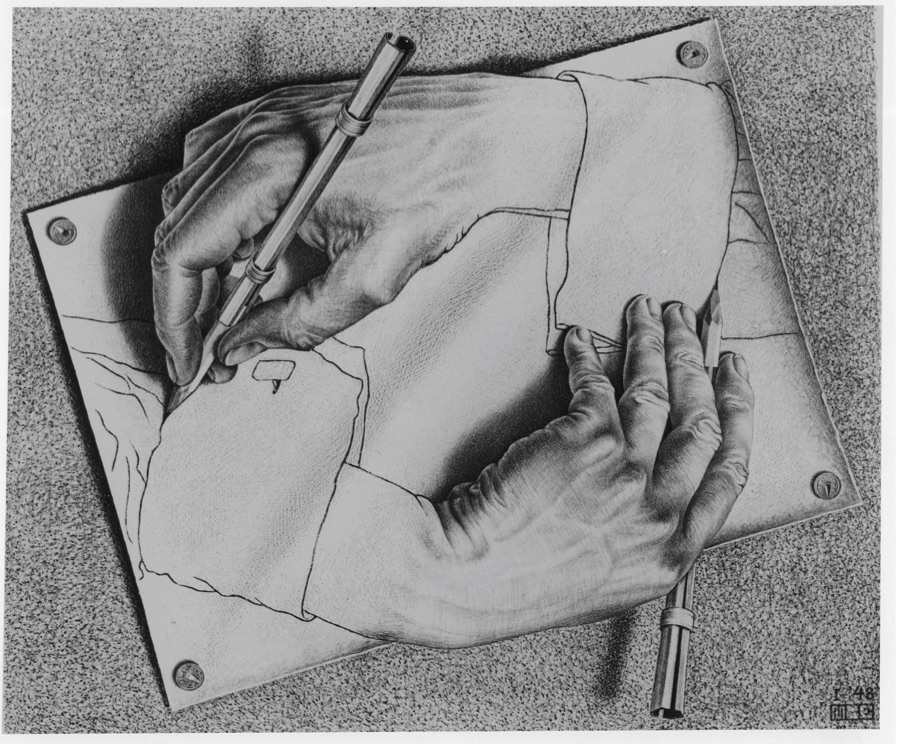

It is in this sense, says Mead, that we always live in a manufactured world. But there is a catch to this: if our most basic manufactured product is perception itself, we are liable to being fooled by our hand-made perceptions; we mistake them for reality. In this sense, the act of sketching gets us close to the world-making our minds are always engaging in. M.C. Escher depicted this long ago in his famous 1948 lithograph “Drawing Hands.” Following Mead’s line of reasoning, this becomes more than just a paradox. It becomes a vivid depiction of the way perception works.

The trouble is that our pleasure in the order and comprehensibility of our manufactured version of reality can distract us from the denser and more chaotic environment we actually live in, whose complexity must always elude our grasp. In many ways the crisis we currently face as a species is a result of this refusal to come out of the closed circle of our world-making. We are more clever at manipulating our environment than we are at understanding the effects such manipulations are having on our own future viability.

The hand has always stood in for creativity–think of God’s hand, gesturing toward Adam in Michelangelo’s great depiction of the creation on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. But the hand has always also stood in for culpability: we speak of being caught “red-handed,” we accuse accomplices of “having a hand in it.” Think of Lady Macbeth, obsessively washing her stained hands. The word “sinister” literally means “left-handed”–as using the opposite hand was considered sneaky, suspicious. The actions of our hands betray us.

And that is the problem. The Latin phrase animating Michelangelo and other great artists of the Renaissance was Homo faber suae quisque fortunae (“Every man is the maker of his destiny”). Yet–in a manner the classical world would have understood very well–we don’t know what our destiny is except in retrospect. We look upon our works and then see who we are. As Robert Lowell says, in the conclusion of his poem “The Dolphin,” “My eyes have seen what my hand did.”

Yet I don’t want to end on that note. There are ways for the hand to proceed through the world which do not assume mastery of it. The hand might approach the world in friendship, for example. Here is William Stafford’s poem “Witness”:

This is the hand I dipped in the Missouri

above Council Bluffs and found the springs.

All through the days of my life I escort

this hand. Where would the Missouri

meet a kinder friend?

On top of Fort Rock in the sun I spread

these fingers to hold the world in the wind;

along that cliff, in that old cave

where men used to live, I grubbed in the dirt

for those cool springs again.

Summits in the Rockies received this diplomat.

Brush that concealed the lost children yielded

them to this hand. Even on the last morning

when we all tremble and lose, I will reach

carefully, eagerly through that rain, at the end–

Toward whatever is there, with this loyal hand.

What we humans grasp is always a fraction of what is there. The open hand must always be reaching for what it can never grasp. We are feeling our way along through the dark for the shape of an unknowable yet tangible world. We must be loyal to it, though it can never be loyal to us.

Discover more from James Armstrong

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Wonderful train of thought and a unique take on “hand”. Stafford’s poem at the end is a powerful and logical bookend to the piece. Thank you!