Independence Rock

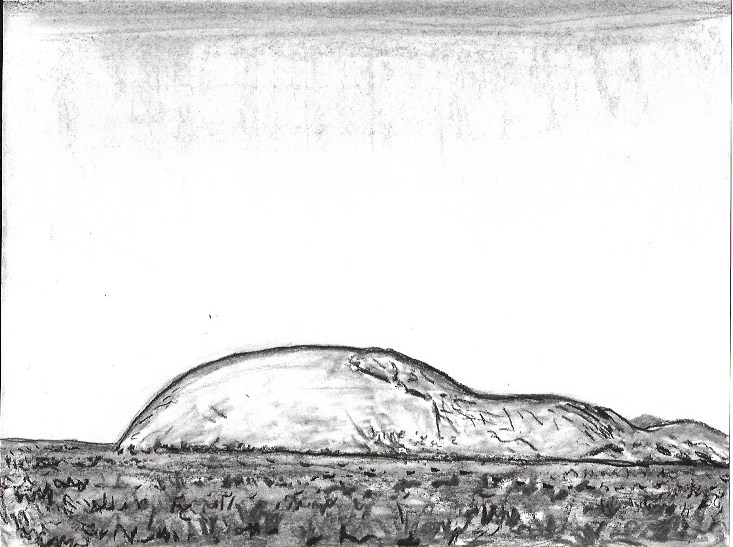

Independence Rock, midway point on the Oregon Trail.

On my journey across the West this autumn I spent some time following the Oregon Trail, the name most people use when referring to a network of old wagon routes heading west from the Missouri River. The trail is really many trails with three main destinations: the Oregon Territories, the California gold fields, and the Mormon settlement in Utah. These destinations represent the diverse desires of those who followed the call of the West: the hunger for free acreage, the hunger for quick profits from mining, the hunger for freedom from the violent enforcement of religious and social conformity in the East. All of these hungers were grouped under the collective Western ideal of “freedom.” The West meant freedom because the West was vast, and the people that lived on it prior to the pioneers–the Indians and Mexicans–were numerically few, were not well armed, and were not politically important.

We now know that “Manifest Destiny,” the feeling of righteousness that accompanied American expansionism in the 19th century, was a suspect brew whose intoxicating spirit masked more insalubrious ingredients: greed, racism and violence. (It is a pertinent question to ask any American who talks about freedom: “Who had it before you seized it?”) But even now, the fizzy excitement of the narrative is hard to resist: the Oregon Trail has become a kind of pilgrimage road which American tourists follow, hoping to recapitulate the heroism and idealism of pioneering, the feeling that Americans had in the mid-19th century that they could once again rise to the challenge, could master the wilderness and make it a fruitful cradle for democracy and independence. Like the Stations of the Cross in a cathedral, the Oregon Trail its marked stages–Chimney Rock and Scott’s Bluff, Fort Laramie, Register Cliff and the wagon wheel ruts at Guernsey, Three Island Crossing and Old Fort Boise–each with its RV-accommodating parking lots and informative signage. As is true of the Stations of the Cross, the Oregon Trail narrative is about suffering and apotheosis: the shared hardships of the Oregon, California, and Mormon Trail provided 19th-century Americans with a religious trial that welded the expanding nation to a common sense of purpose. The Oregon Trail both facilitated and justified the nation’s new imperium, which by the 1860s extended from sea to shining sea.

Independence Rock, seen above, was significant to the wagon trains crossing the Wyoming plateau because it was the half-way point of the trip for many of them. Pioneers sought to reach it by July 4 because if they arrived much later than that they risked being cut off by early snows in the mountains–the fate suffered by the Donner party. Travelers who camped at Independence Rock often carved or painted their names on its smooth granite flanks–soon there were hundreds of names, so many that Jesuit father Pierre Jean de Smet christened it the “Great Register of the Desert.”

But the emigrant trails followed previous trails–valleys cut by rivers winding their way across the arid land; paths made by the buffalo, and by the Indian following the buffalo. The landmarks were old landmarks, had stood in human memory for thousands of years. If they became, for the westward emigrants, icons of a Western “Exodus” narrative, that was only their most recent significance. Humans have probably been carving symbols on the rock for millennia. There are many petroglyphs found across the West; they are usually images of deities, and are thought to be connected to the Indian practice of the vision quest. By contrast, Americans thought it was important to leave their individual names–a reflection of the value they placed on the individual and also evidence of the impoverished egotism of that belief. Topographical engineer Capt. Howard Stansbury said at the time that emigrants must have felt, “judging from the size of their inscriptions, that they would go down to posterity in all their fair proportions.” The one example of someone carving something more significant than an individual name was the cross John Frémont cut into the rock while passing by on his famous 1842 surveying expedition. But subsequent pioneers blasted the cross off the cliff face, mistakenly believing it to be the work of a Catholic.

At any rate, the names are temporary–the rock is continually sandblasted by the wind and lichen also works to erase the Register. A millennium from now, Independence Rock will again be a nameless whaleback of archean granite. And what of our nation, and its love of freedom and individualism? Will we have learned to overcome our youthful boastfulness, our possessiveness, our violent egoism? The dangerous years ahead will require a degree of sacrifice and cooperation Americans are not at all used to. Will we have managed to pass through the bottleneck of climate change with a new understanding of what it takes to survive on this earth? Will we have learned that freedom is attached by the hip to social solidarity? Or will we be a vanished people, leaving behind a few stainless steel machine parts and windrows of plastic trash, while, as the poet Shelley put it in his poem “Ozymandias,”

. . .boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

Discover more from James Armstrong

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.