Into the Woods

My friend Kurt Cobb’s recent essay, found here, posits an epistemological divide between”two main ways of knowing in our modern culture: 1) the rational, reductionist way and 2) the holistic, relational, intuitive way.” The first way is dominant in Modernity–in fact defines it. Our “institutions, scientific, economic, financial and organizational” are organized by this mode of thinking, says Cobb. But that dominance is increasingly challenged by the inherent limitations of the reductionist approach. Cobb says:

For the reductionist thinker, everything in the universe is made up of parts. If we can understand the parts, we can understand the whole. Depending on the field, the physical world is nothing but atoms and molecules and the social world is nothing but self-maximizing, rational actors. The reductionist view is very powerful and filled with “nothing but” statements. It never occurs to the thoroughgoing reductionist that the idea of “parts” is merely a mental construct.

The latter statement is crucial. A “part” is a consequence of thinking, not an actuality. Just as a “thing” is a product of perception (see my previous post, “The Loyal Hand”). We see parts as a result of our way of making use of the world. But it is equally valid to see the world as a whole, as a network of relationships in which no “thing” exists in isolation, no “part” exists without the interchanges of matter and energy that create and maintain it. This means that the clarity of thinking we associate with reductionism–the simplification which results from ignoring almost everything but the part we are interested in–is instrumental. It is applicable in a local way, to effect certain particular changes. But we can’t predict with certainty how our actions will ramify through the whole system we are interacting with.

This is what makes our present predicament so “wicked,” to use a term from social planning. A “wicked problem” is one that is “difficult or impossible to solve because of incomplete, contradictory, and changing requirements that are often difficult to recognize,” according to Wikipedia. We see this kind of problem cropping up everywhere now. As Cobb says,

We may wish fervently to address income inequality or hunger or climate change. But the complex interactions and power arrangements in our global society make it difficult to do anything but make a small dent. Even our personal destinies seem to be caught up in a flow of events which we cannot control, but rather must react to.

A world of intractable, ramifying difficulties is a far cry from the technical Utopia that we were promised as recently as the 1960s, when it was thought that most of the world’s ills would be solved by reason and technology. It is the abiding thesis of this blog that we do not know where we are. We Moderns think we live in a “clean, well-lighted place,” to crib a line from Hemingway. In reality we live in a dark thicket, a Gordian knot of forces interacting at a level of complexity which renders vain any hope of total comprehension, any dream of total control.

Modernity begins with the belief that humans are constrained, but could be free. By hacking away at the choking weeds of superstition, religious dogma, and social cant, humans could stand in the sunlight of an open field. Armed with the scientific knowledge of nature we could remake the world as a human paradise. But the world is not dead, or passive, or simple. It is alive, active, and infinitely complex. Any clearing we make will soon be challenged by all the agencies we share the earth with. That is an insight that comes from the other way of thinking Cobb describes. As he puts it, holistic thinking “tries to see the entire picture including all the messy consequences. Knowing that those consequences ramify infinitely, it can only intuit the extent and significance of any pattern. The holistic way knows ahead of time that it will never see the whole, only ‘feel’ its meaning.”

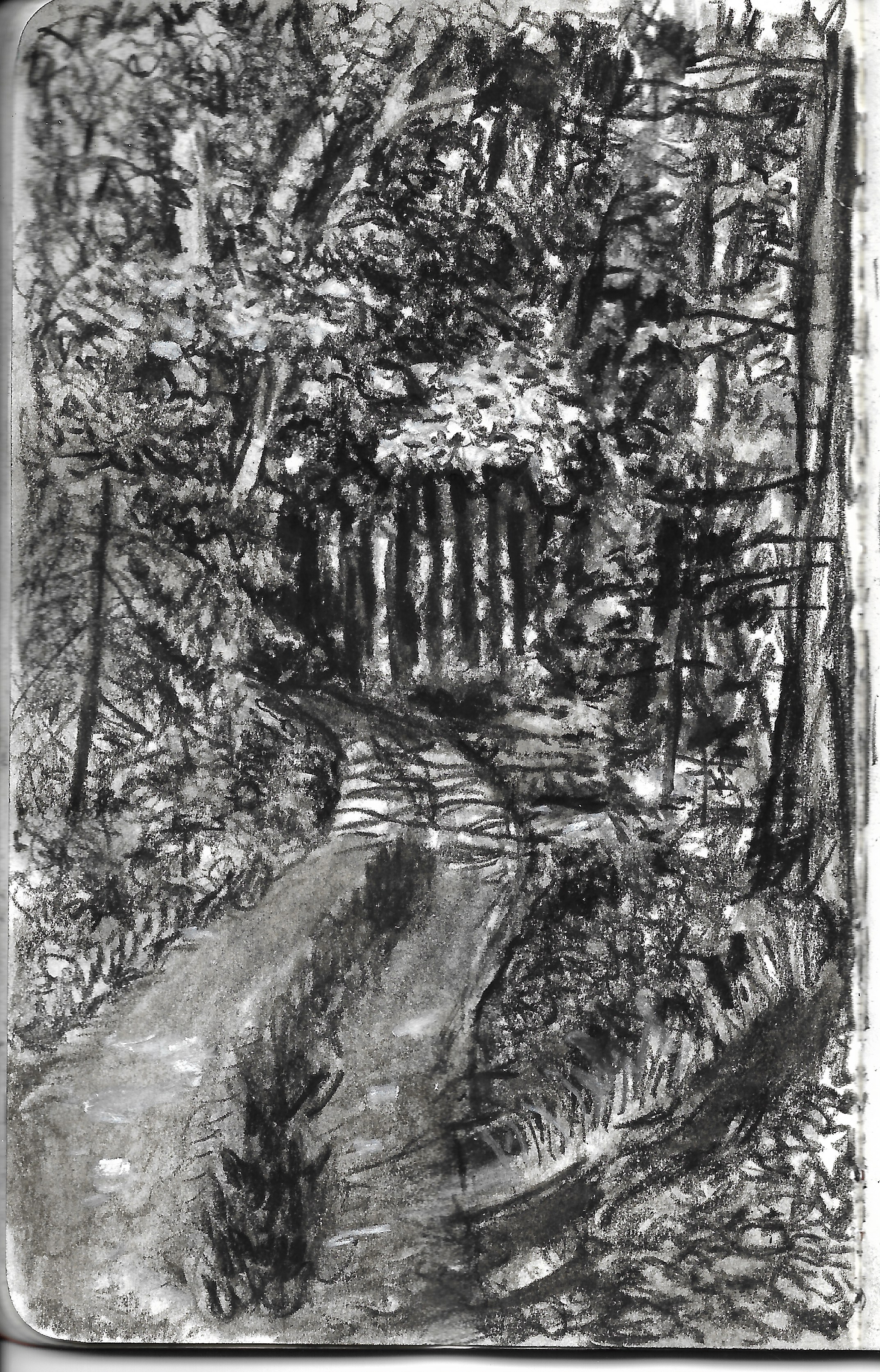

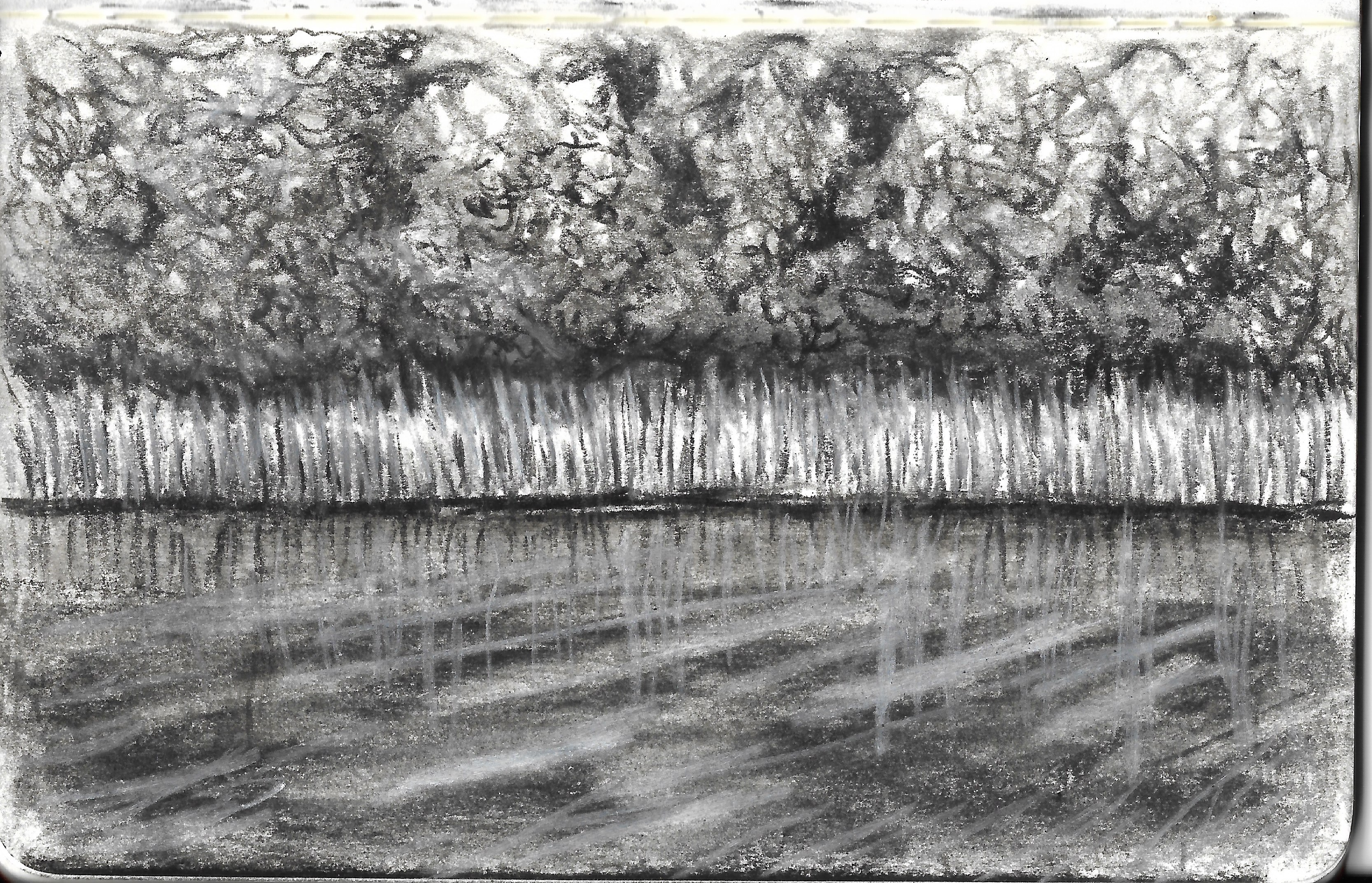

The main critique of Modernity has come from the arts, which champion holistic thinking. The trajectory of experience in any of the arts is toward “feeling” a meaning rather than merely engineering an effect or presenting an argument in a didactic fashion. To immerse oneself in an artistic practice is to open oneself up not to mastering the materials (although there is a component of mastery in learning the techniques required) but to being mastered by them. At a certain threshold of proficiency one glimpses a complexity one can never exhaust–it is that exhilarating sense of constant discovery of new meanings that makes art so exciting. But this also makes art a spiritual venture. If Modernity reduces to control, art reduces to complicate. A drawing may reduce the world to a few lines, but those lines gesture toward a world that will never be exhausted, or controlled, by a few lines.

I am including here two drawings I made this summer, camping in northern Minnesota. The first is of a forest path in Bear Head Lake State Park. The second is on the Tamarac River at Big Bog State Recreation Area. These drawings are attempts at expressing the feeling I get when confronting the dense complexity of the world.

Discover more from James Armstrong

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.