The Sound of a Painting . . .

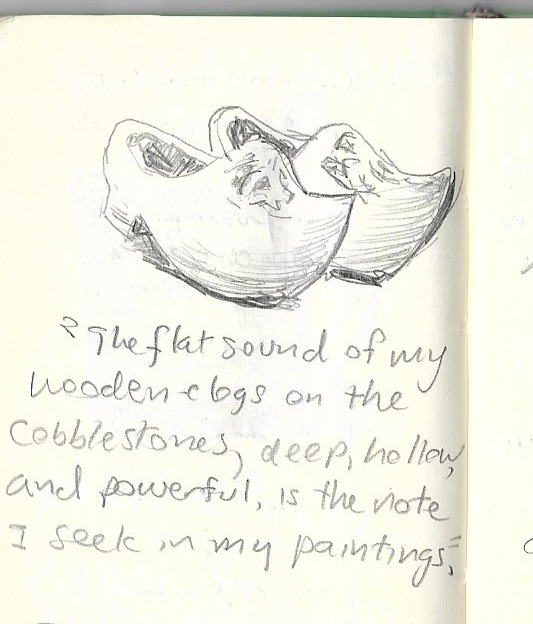

This quote is from Paul Gauguin–I wrote it down while visiting the “Gauguin: Artist as Alchemist” exhibit at the Art Institute of Chicago. The exhibit displayed aspects of Gauguin which you usually don’t see–his work as a wood carver, print-maker and potter. Beside many of his more famous paintings were objects he had chiseled from wood or sculpted from clay. I was struck by the pair of shoes he had made for himself during his time in Brittany–and I was intrigued by the idea that a sound could guide a painter. As I reflected on it, I realized that it explains a lot about Gauguin’s work. He wanted his paintings to be heard, not seen.

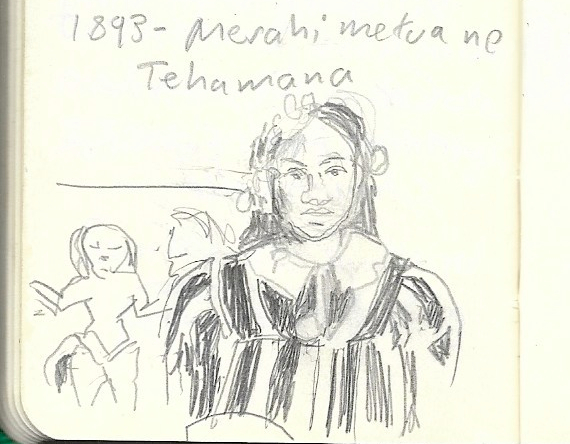

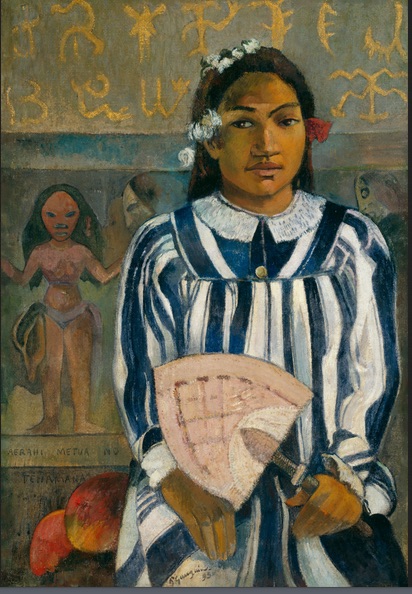

I have always been a fan of Gauguin–when I was a young man I kept a print of his painting Merahi metua no Tehamana on the wall of whatever apartment I was renting. I was happy to see the original of that painting in the Chicago exhibit, and it was as I remembered: a brooding young woman in a blue-and-white striped “mother Hubbard” dress, a red gardenia behind her ear, stares at the viewer. Behind her are mythical figures and mysterious glyphs.

What is remarkable about Gauguin is his use of flattened perspective and bold, simple colors: he turned his back on the meticulous realism of the French Academy, much as the Impressionists had done before him. But his paintings are not just “impressionistic.” The Impressionists were keen to give a full account of light–adding time and motion to painting, emphasizing the ephemeral effects of light, privileging color and texture over outline. They wanted to find a way out of the static realism which Western art seemed trapped in. But their solution still assumed the Modern notion of objectivity–they just developed a more fluid kind of objectivity, one that reflected a sophisticated understanding of how human perception grasped the world. Gauguin’s interests were different: he was looking for a way to express the intensity with which the world grasped human perception. He was interested in the world’s agency. He was interested in myth.

The difference between seeing the world and hearing the world is profound. Sight is directive: you look at something. Sight encourages the notion that the world is secondary to your intelligence and your will. Hearing reverses that dynamic: you listen to something. You are a recipient of sound. In fact, you often hear a sound before you know what its source is. This is why a sound can frighten us–sound is omni-directional but sight is only in one direction. Sound is also penetrative, corporeal. Light waves are invisible, but sound waves are palpable–there is no separation between a sound and your hearing of it. You can pretend to be a disembodied viewer, but you can’t be a disembodied hearer. Sounds are profoundly wedded to their environment, as they are shaped by the space around them. While every sound has a distinct source, sound waves can be immersive, engulfing: can echo and reverberate. When a sound reaches you it not only bears information about its source but also about the space it has traversed.

We always acknowledge that images–real as they seem–are on some level merely a trick. They are made of reflected light. The source of a color or a shape is ultimately the sun–which makes vision oddly spectral. It is imaginary–from the Latin “imago,” meaning “image or likeness.” The world is appearance, and appearances deceive. But sound is always genuine. It begins with its source. We can mistakenly identify a sound, but we don’t feel that it is an illusion. Even when it is a recording, it is still a sound, not the image of a sound.

Part of that is because sound is already an abstraction–it lacks the comprehensiveness of sight. It carries less information–which is why it’s easier to store music on your computer than it is to store movies. But it is also less likely to be confused for something bigger than what it is, which means (in systems theory terms), it can point away from itself to the larger, ever-unknowable world. To say that something speaks implies it has to be interpreted. A picture may be worth a thousand words, but that means that a picture can dominate the conversation and silence the viewer.

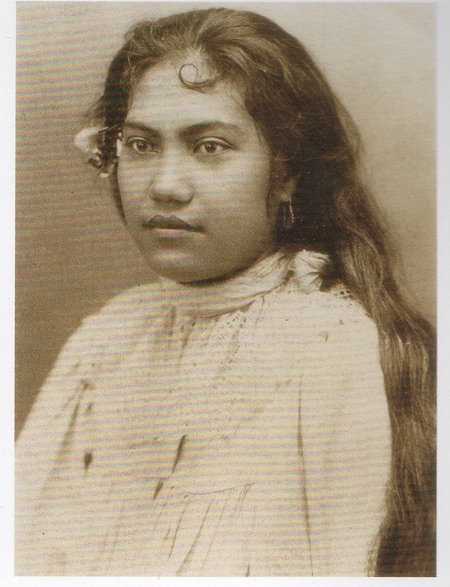

Gauguin simplified his paintings, reduced them from elaborate imitations of the “real” to more abstract designs; his colors and lines speak more directly, the way sounds do. But like sounds, his designs are not complete worlds. His paintings point, not to themselves, but to the mysterious world that is their origin, the way sounds turn us toward an environment and ask to be interpreted. A photograph of a Tahitian woman may resemble her quite accurately, but it doesn’t doesn’t sound like anything. It is silent in the sense that there is nothing more for the viewer to say.

One of my justifications for this blog is to express a central claim: our technology has fooled us into believing we can accurately depict, and therefore control, the world. But the meaning of the Anthropocene–and its looming global blowback–is that the world has always been opaque to us. If we now live in the age of “unforeseen consequences,” then we have never seen clearly enough. There is more truth in a sketch than in a photo, therefore: the sketch contains the trace of the actor, and exposes the incompleteness of the action. A painting may say more than a photo because it says so much less. What it does say, you might be able to hear.

Discover more from James Armstrong

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.