Danger, Will Robinson!

Apparently Netflix has decided to reboot the 1960’s series Lost in Space. Coincidentally I have been watching the series on Hulu–something to do while washing dishes. But since a side interest of mine is science fiction film, I’ve actually been doing a lot of thinking about the show and its place in American culture.

Two television series made a huge impression on me when I was in grade school in the 1960s. One was Star Trek, Gene Roddenberry’s paean to the space age (1966-69). That show has worked its way deep into the Modern psyche, spawning a vast empire of spin-offs and novelizations and Comic Con costumery. The other was Lost in Space (1965-68), which has inspired only one really terrible movie (1998). But I have to admit, as I re-watch the serial episodes of Lost in Space, that it was just as important to my young mind as the more cerebral and adult Star Trek. In fact, I was surprised how viscerally I remembered those early episodes which depicted the Robinson family, their pilot Don West, the stowaway Dr. Smith, and the barrel-shaped, lobster-clawed robot that served as Smith’s comic foil as they struggled to survive on a desert planet unknown light years from earth.

What strikes me forcefully, seeing the show as an adult, is how utterly preposterous the premise of the show was and yet how completely appropriate it was to the American experience in the 1960s. For starters, sending a nuclear family into space to colonize a distant planet in a ship no bigger than a split-level suburban house is crazy–the fuel and supplies alone would require a vessel many times bigger. The pie-shaped “Jupiter 2” spaceship bears a superficial resemblance to the flying saucers of Forbidden Planet and The Day the Earth Stood Still, two 1950s films that made science fiction respectable in a decade of bug-eyed-monster movies intended for teenagers at drive-ins. But in producer Irwin Allen’s version, the ship was like a magician’s hat–the Robinson family is constantly pulling various items of heavy equipment–including a full-sized caterpillar tractor vehicle–out of a space that could have barely contained the family’s luggage. Yet the size of the ship is oddly appropriate: the real forebearer of the Jupiter 2 is Disneyland’s “House of the Future.” This was a sleek modular pod built entirely of plastic components–everything from the fiberglass outer shell to the polyester couch pillows– and stuffed with technological innovations such as a microwave oven, an “ultrasonic dishwasher,” an intercom system, and modular sinks that raised and lowered to accommodate the height of the user. The House of the Future was a joint project of Disney, the Monsanto Corporation and M.I.T.–and was intended to be a 3-D sales pitch for the home products that would soon flood the market. The Robinson family is on some level doing what most American families did throughout the 1950s and 1960s–leaving our crowded post-war American cities to colonize the wilderness of subdivided farmland, moving into ranch houses and split-level Cape Cods that looked as if they had been dropped from the sky.

In that sense, the “space” of Lost in Space is part of a social fantasy. After twenty years of collectivism, which enabled America to survive first the Great Depression and then the Second World War, America was reverting to its individualist ethos with a vengeance. And that meant the return of the frontier as a trope. One of most popular genres in this period was the Western–I remember very well the ubiquitous cowboy shows on television–Bonanza, Gunsmoke, Maverick, The Rifleman, etc.— and the CinemaScope horse epics in the movie houses. Another important TV show of the time returned Americans to even earlier frontier experiences: I was an avid fan of Daniel Boone, which was itself inspired by the Disney film Davey Crockett, both starring Fess Parker. America has always been able to romanticize the frontier as the source of its virtue. The “untamed wilderness” is the necessary condition to American individualism, as unclaimed spaces provide the opportunity for advancement without the visible presence of politics. A man and his family can carve out a living in the forest or on the plains, or so the story goes. Frontier space is the theater for the realization of the libertarian dream, since there is nothing to interfere with the natural relationship between hard work and bountiful results (the prior claims of indigenous people notwithstanding).

But by the 1960s we had run out of wilderness–so we naturally turned to spaces beyond the planet. It is no accident then that John F. Kennedy called space the “New Frontier,” a phrase Captain Kirk echoes in Star Trek‘s opening monologue, when he calls space the “final frontier.” The “space” everyone is talking about is not a place, but an ideology of expansion. In America this usually translates into a denial of the frustrations and limitations of community. When social conflicts become acute, Americans are tempted to imagine they will “light out for the territories,” as Huck Finn puts it. Just start over somewhere further west. This was the story of the 1960s, as the suburbs became the easy solution to the social problems of the American city. The Robinsons are, according to the story line of the show’s pilot, fleeing from an overpopulated, polluted earth, trying to start over again in a new land–and this was just a mirror image of the flight from urban spaces.

It is important at this point to remember that the precursor to Lost in Space was the Swiss Family Robinson–the 1812 novel by Johann David Weiss. Weiss’ book is the source not only of the Robinson family’s name but also the show’s basic plot predicament. In Weiss’s story, a family en route to Australia is shipwrecked on an island in the East Indies. They manage to salvage supplies from their ship and set up camp on the island, surviving by dint of their fortitude, intelligence, and faith. In fact the book was intended to teach children “about family values, good husbandry, the uses of the natural world and self-reliance,” according to Wikipedia. The assumption underlying these didactic lessons is that unclaimed spaces are testing grounds for God’s providence; the world is so constructed that well disciplined and rational protestants can thrive.

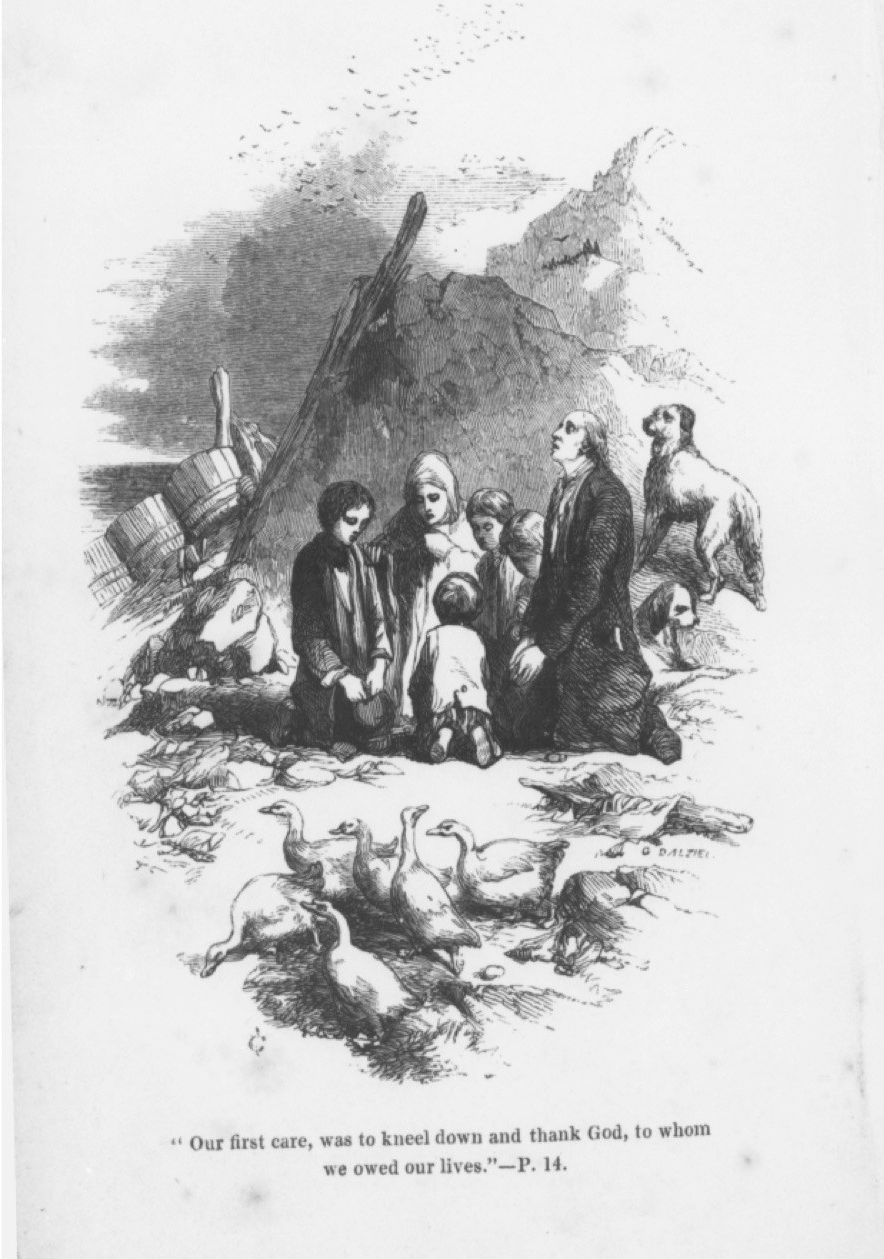

This is the piety of empire. The characters in Weiss’s book survive because they salvage guns and domestic animals from the ship they came in. They proceed to dominate the “empty” space around them with their technology and their agriculture. This is the project of Europe throughout the 18th- and 19th- centuries, and this is how we envision the extension of our civilization into outer space. It is our “manifest destiny” to spread ourselves across the stars. Here is a grainy still of the Robinson family replicating the Protestant piety of the original story. In Episode 5 of season one, the family has survived a perilous sea journey and when they are safely on land, Maureen Robinson hands her husband a Bible and they form this somewhat awkward tableau.

The difference between the Swiss Family Robinson and the Space Family Robinson was that the Swiss Family Robinson was making itself at home on earth, a planet on which it had evolved and to which it was admirably adapted. The characters in Lost in Space inhabit a world singularly hostile–it has an eccentric orbit which causes it to swing wildly between hot and cold. Also they did not bring with them domestic animals or the tools to create the kind of agriculture they would need to survive. There are scenes showing them planting a little garden bed, the kind that suburbanites toy with in the back yard. But the planet’s hostile climate would have made any farming problematic.

And that is the point I made at the outset: this expedition is not really equipped to be self sufficient, any more than the new suburban pioneer is equipped to use his yard for anything but an ornament. The actual biological basis of America’s highly industrialized civilization had, by the 1960s, become invisible to most people. Food appeared in grocery stores, water from a tap. Whereas the original Swiss Family Robinson story was intended to teach “husbandry” and methods of self-sufficiency, its 20th century successor was perfunctory at best in its treatment of such subjects. The original story was intended to teach the reader something about life on earth. Lacking an earth, Lost in Space must fall back on family drama and a constant supply of hostile aliens–much as the westerns of the 1950s and ’60s were never about animal husbandry but about fighting Indians or “bad guys.”

I have always found it curious that the setting of John Ford’s classic westerns is Monument Valley on the Arizona-Utah border. Having lived in the Valley myself I know it is high desert, not much good for farming (without irrigation) and not even great for ranching. The Navajo manage to scratch out a living with sheep and goats. But Ford was attracted to the cinematic qualities of the place–its barrenness, its fantastic rock formations. These formed a compellingly alien backdrop to his stories of bloody confrontation. In similar fashion, Lost in Space envisions its foreign planet as largely desert. Though there are jungle scenes, and there is an ocean, the Jupiter 2 sets down in a landscape very similar to that of a John Ford movie. The spaceship becomes the lonely ranch house, the outpost of civilization, ever vulnerable to hostile interlopers.

Space, that is, has become increasingly empty in the American imagination. Like the “white spaces” in 19th-century European maps of Africa, the landscape is blank to signify its availability. Something we can write our destiny on in large letters. Something we can fill with our desires and dreams. The problem is that such spaces are only in the imagination. A desert is only seemingly blank–its geology and ecology are real and complex and easily disrupted. Even outer space is not really empty–it is, for example, full of fierce radiation which, as we are finding out in our plans for a mission to Mars, makes any long-term voyage through it very problematic for living beings. Thus our willful simplification of space can hide many dangers–and can also become a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy. As I write this entry, the American territory of Puerto Rico has been utterly devastated by hurricane Maria. People are trying to survive without electricity–thus without clean water or food or air conditioning or medical help. What was in the tourist brochures a tropical paradise has become a hostile desert–the forests stripped, the cities decimated, roads and power lines out of commission, and (most tellingly) the small but promising agricultural sector utterly debilitated. Overnight Puerto Rico has become the dystopian future that many contemporary science fiction novels predict. And of course the energy that amplified Maria’s destruction was provided by our collective inability–and when I say “our” I mean Americans–to face the reality of climate change. Ignorance makes its own deserts.

To be lost in space is to not know where you are. We imagine we are in a providential narrative of inevitable progress and perpetual expansion. That very assumption is not only blinding us to our true position, it is actively working to make the one space we really occupy more and more hostile to us. We are increasingly living on an alien planet–one which we ourselves have alienated.

The one surviving meme from Lost in Space depicts the robot waving his arms wildly and shouting “Danger, Will Robinson.” The comic paradox of an assumedly unemotional machine hysterically gyrating like an overwrought metallic version of Oliver Hardy is what makes the meme stick in the mind, I suspect. But the robot’s warning takes a more sinister tone in my own consciousness. Part of the robot’s function is to act as a kind of cybernetic guard dog for the family. Its sensors are always interrupting the Robinsons’ sense of equanimity by detecting dangers just beyond their ken. The happy nuclear family does not know what is coming. Will it heed the warning? Will we, lost as we are?